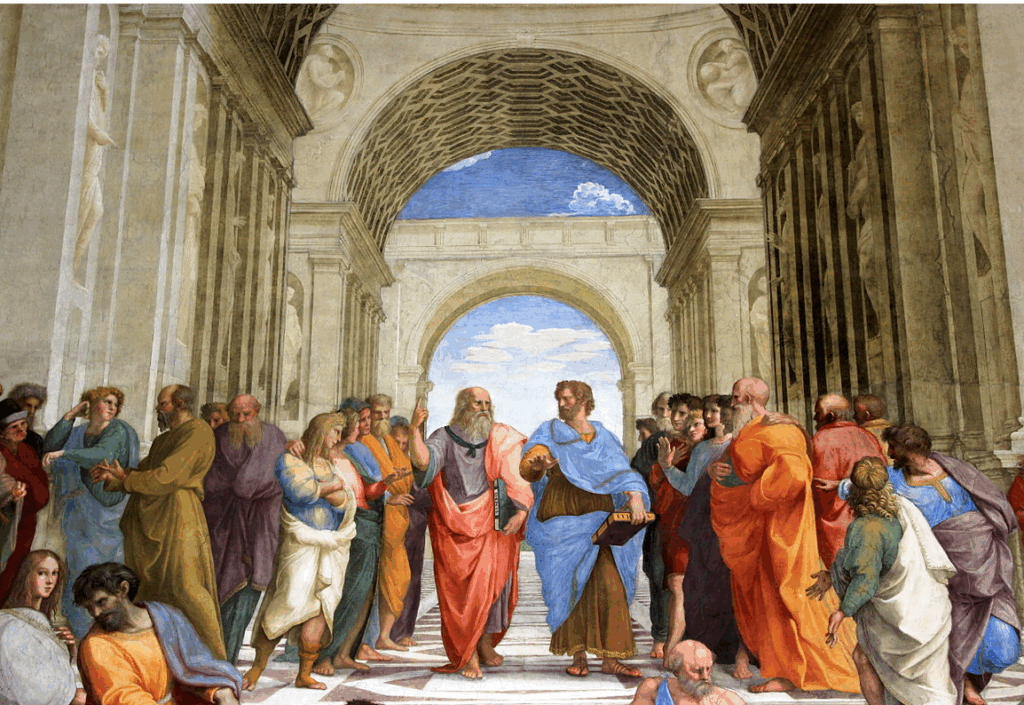

Photo: Raphael, The School of Athens (detail), antigonejournal.com

Narrative imagination is an essential preparation for moral interaction. Habits of empathy and conjecture conduce to a certain type of citizenship and a certain form of community: one that cultivates a sympathetic responsiveness to another’s needs, and understands the way circumstances shape those needs, while respecting separateness and privacy.

Martha Nussbaum, Cultivating Humanity

I spent the better part of my freshman year many years ago participating in Stanford University’s Structured Liberal Education program. It was a transformative experience. I vividly recall taking a break in my reading of Plato’s Republic, specifically the pages where Socrates denies poets a place in his ideal state, and feeling—along with anger—a sense of sublime awe at participating (albeit unbeknownst to Socrates) in a philosophical conversation that stretched back millennia. At the time, I was leaning over the large central well of the university’s undergraduate library and have often mused since about what part vertigo might have had in that feeling of awe. That central well is now long gone, having been replaced in the 1990s by extensions of the original floors to house research centers and institutes. But the experience of profound connection remains.

What is the role of “liberal education” today? In the face of growing student and parent inclination toward professionally oriented majors, countless scholars, university presidents, journalists, and professional organizations have written defenses of that “distinctively American article of faith” that is liberal education (Mintz). Their arguments typically evoke the ways in which broad humanistic training promotes independent thought, sound judgment, an ability to weigh conflicting evidence and challenge prevailing norms, an appreciation for historical perspective, cross-cultural awareness, competence in negotiating competing value systems, strong problem-solving skills, and effective communication. Often referring to the work of philosopher and progressive educator John Dewey, they reject both our “modern forms of narrow vocationalism” and the belief that liberal education fails to prepare students for the demands of their future professional lives (Roth 165). More recently, Joseph Aoun and others have called for humanistic educators to prepare all students “for life with AI,” so as ultimately to advance “human well-being in a digital world” (“Higher Ed”).

I trust it goes without saying that I am broadly supportive of these arguments. A few years back, I co-led the first major reform of American University’s core curriculum in 27 years and, in the process, was inspired by much of this work, especially the extensive body of studies and reports produced by the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Photos: Harvard University Press; Sally Ryan, Wikipedia

How does wisdom fit into all of this? In her Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, philosopher Martha Nussbaum takes us back to Seneca’s Rome to show that the concept of studia liberalia, liberal studies, has long been pulled in two distinct directions. Against those who understood the word liberalia to reference a style of education that initiated propertied “freeborn gentlemen… into the time-honored traditions of their own society,” Nussbaum writes, Seneca promoted education that produces free citizens—”[m]ale and female, slave-born and freeborn, rich and poor”—allowing them “to take charge of their own thought and to conduct a critical examination of their society’s norms and traditions” (293, 30).

Following Seneca and his Greek Stoic counterpart Epictetus, Nussbaum recognizes that study of the so-called great books is valuable in that it makes the mind “more subtle, more rigorous, more active” (35). But the great books should not be elevated, as has so often been the case, into cultural authorities, “objects of veneration and deference” (35). And the canon itself must be understood to be highly dynamic. Today, as it was for Nussbaum, that means opening the canon up to the cultures of the world; to more works by women and minoritized authors; and to a more concentrated focus on the lives of the poor and the powerless. In short, Nussbaum’s conception of liberal education, to which I subscribe, is a long way from Harold Bloom’s defense of the traditional canon, in which the highly contestable notion of “aesthetic superiority” attempts to absolve the great books tradition of the charge, in Dewey and others, that it is “elitist and archaic” (Mintz).

Nussbaum’s project writ large is to make the case, in the manner of Socrates and the Greek Stoics, for a practice of philosophic questioning “woven… into the fabric of [our] daily lives” and fully conducive to the ideals of democratic self-government (17). Time and again, her call for educational practices by which students will learn to cultivate their humanity dovetails with what I am calling, following Sternberg, teaching for wisdom. “Cultivating our humanity in a complex, interlocking world,” Nussbaum writes, “involves understanding the ways in which common needs and aims are differently realized in different circumstances” (10).

Critical to the project that gives Nussbaum’s book its title is the cultivation of what she calls the “narrative imagination”—”the ability to think what it might be like to be in the shoes of a person different from oneself, to be an intelligent reader of that person’s story, and to understand the emotions and wishes and desires that someone so placed might have” (10f.).

Photo: Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study

The “habits of empathy and conjecture” that one acquires in exercising the narrative imagination, Nussbaum writes,

conduce to a certain type of citizenship and a certain form of community: one that cultivates a sympathetic responsiveness to another’s needs, and understands the way circumstances shape those needs, while respecting separateness and privacy. (90)

As children grow into adults, she continues, the development of their narrative imaginations leads to increased awareness of their “own vulnerability to misfortune” and, as a result, to their increased capacity for compassion (91).

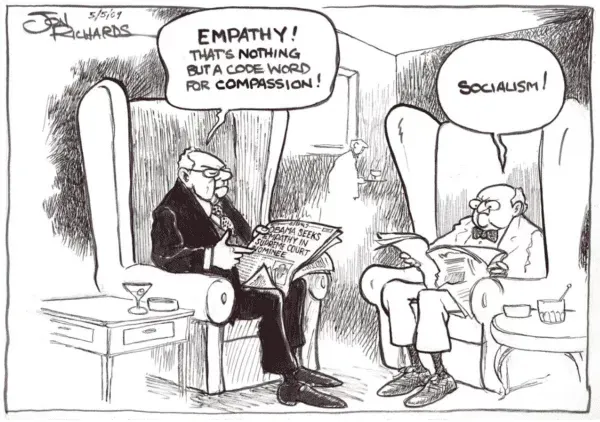

Nussbaum published Cultivating Humanity in 1997—eight years after Fukuyama authored “The End of History?” and just three years after Timothy McVeigh and his co-conspirators bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in retaliation for the US Marshals Service’s siege at Ruby Ridge. Today, the anger that fueled the 1990s militia movements and led to the Oklahoma City bombing has sadly seeped into our political mainstream. Identity politics, which Nussbaum takes to task for running counter to the “goal of producing world citizens,” is still highly entrenched in both academia and the public sphere, although far more weighted to the right today than it has been in the recent past (109). Ditto for the related tendency to reduce democracy to “merely a marketplace of competing interest groups, without any common goals and ends that can be rationally deliberated” (110).

In almost every respect, the aims of Nussbaum’s proposed reform in liberal education dovetail with the project of reading for wisdom through a rich array of diverse narratives as outlined in these pages. Where I differ from Nussbaum nearly thirty years on, as well as from my contemporary colleagues at AAC&U, is around the continued use of the word “liberal”.

There is value in understanding the millennia-old tension within the concept of “liberal studies”—between that which initiates gentlemen of means into their station in life and that which is befitting of all citizens, of the nation and of the world—as well as the tension inherent in “liberalism” between valuing individual liberty and property rights on the one hand and valuing equality before the law and promotion of the common good on the other. Indeed, both forms of tension point to the sort of richly contextual conflict of interest and values on which the exercise of wisdom thrives. But we clearly need to move beyond the historically classist conception of liberal education and the still-widespread elevation of individual liberty and property rights into absolutist goals.

Having spent nearly two decades explaining to students and parents, both prospective and current, that liberal education is not leftist indoctrination and that the liberal arts involve far more than what we think of as the arts today, I believe it is time to let “liberal” go as a descriptor of the style of education we seek to practice. In recent years, we have seen a salutary shift in the way universities think about their general education curricula—away from the focus on disciplinary divisions that gave us distribution requirements and toward an emphasis on the skills our students will need in their future careers and civic endeavors. It is now time, I would argue, to move away from the traditional emphasis on “liberal education”—a concept that is every bit as much ‘inside baseball’ to the non-academic as those of the “humanities” or the “social sciences”—and toward “wisdom” as an attribute that will serve our students well in their future professional and personal lives.