Wisdom is a perfect antidote to the paranoid style of American political culture today.

The genesis of this blog dates back to the spring of 2018 when, after 11 years as a dean at two universities, I was granted a semester-long sabbatical from my position as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at American University. Prior to taking on that deanship, I had worked on a multimedia project entitled We the Paranoid. You can view version 1.0 of it here. In many ways, the decision to use my sabbatical to work on wisdom grew out of the perception that, between the late 2000s and 2018, the paranoid style in contemporary American culture had become too ubiquitous, too self-evident, and far too toxic, and that the cultivation of wisdom was in fact its most powerful antidote. The passage of time has only intensified that feeling.

One of the stories that We the Paranoid told was of the pleasure that ostensibly normal, non-delusional viewers—viewers like us—take in coming to believe in the conspiratorial fantasies of a narrative’s male protagonist. In a common version of this conversion plot, our coming-into-belief as viewers is anticipated by that of a strong professionalized woman—Kathryn Reilly in Twelve Monkeys, Alice Sutton in Conspiracy Theory, Dana Scully in The X-Files—who, over time, falls for a conspiracy-obsessed would-be action hero (We 3.4).

A salient characteristic of the paranoid style of 90s and 00s entertainment media, We the Paranoidargued, is that it invites the viewer to enjoy the ego boost that paranoiacs crave—the conspiracy-minded hero is saving the world after all—but to do so in that mode of split belief that psychoanalysts call disavowal (2.3). We “know very well” that the conspiracies espoused by the narratives’ action-hero protagonists are absurd, “but all the same” we lend them credence in the interest of narrative pleasure (Mannoni 70).

Seen from the vantage of 2018, and still more so today, this conceit feels quaint. What has changed?

In the 90s and 00s, the paranoid style of the militia or 911 Truth movements could still be seen as largely the province of a lunatic fringe. I dare say I was not alone in chuckling at the Militia of Montana’s claim that a map of America on the back of a 1993 Kix cereal box laid out the New World Order’s post-invasion plan for carving the United States into eleven regional departments (Fellis). And how could one reasonably argue, with 911 Truth, that the Bush administration brought down the Twin Towers when they could not fake evidence of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction (We 4.15)?

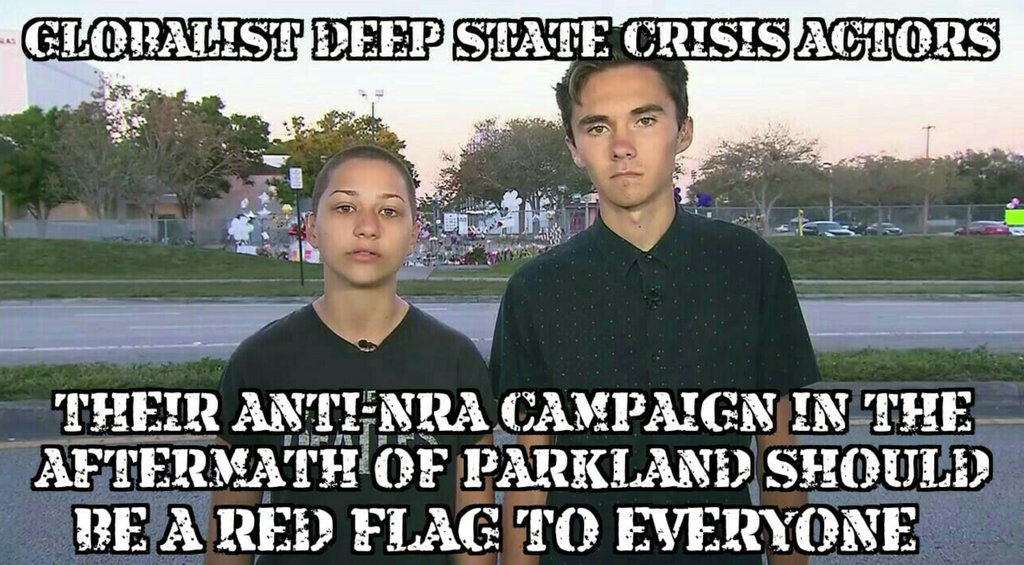

Today’s paranoid style, however, no longer feels like fun and games. The last several years have treated us to claims that DNC staffer Seth Rich was murdered by MS-13 goons hired by Hillary Clinton for leaking her campaign’s emails (Inskeep); that the Mueller investigation was actually a cagey ploy on the part of Donald Trump himself to “drain the swamp” (MAGA); that the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary was staged and the survivors of the Parkland shooting were “crisis actors” (Romo); that the Covid-19 pandemic was a “tool for Jews to expand their global influence” (ADL); that the FBI instigated the insurrection of January 6, 2021 (Jackman et al.); and that the state of Israel is now run by a “cabal of satanic pedophiles” (Rosenberg).

During the 2024 presidential campaign, voters were told that President Biden and the Democratic Party orchestrated the assassination attempts against former President Trump (Karni); that hurricanes Helene and Milton were “weather weapons” deployed by the U.S. government (Warzel); that the “deep state” may have used an atmospheric research facility in Alaska to engineer a snowstorm over Des Moines and so rig the Iowa caucus (Nichols); and that, in the aftermath of Helene, Kamala Harris “spent all her FEMA money, billions of dollars, on housing for illegal migrants” (Gore)—to name just a handful of the more egregious conspiratorial claims.

Hillary Clinton’s take-down of then-candidate Donald Trump as an “Id with hair” beautifully captured the way Trump, like Freud’s unconscious, is blind to contradiction (Dowd). But Trump also exemplifies the paranoiac Ego: self-centered to the point of megalomania, chronically prone to savior fantasies, and quick to project its sins and shortcomings onto others—to the point where Freud’s understanding of “projection” has now entered common parlance. When candidate Trump claimed, at the 2016 Republican National Convention, that “I alone can fix it,” he (wittingly or not) echoed the world-savior presumption of countless conspiracy-minded action heroes of decades past (Applebaum). Trump’s subsequent release of two rounds of digital trading cards portraying himself in superhero guise only made the implicit explicit.

Polling around the 2024 election clearly indicated that disavowal was operative in some elements of Trump’s base, who “know very well” that their candidate plays fast and loose with the truth, but follow him “all the same” because… [insert reasons here]. No recent event better exemplifies the passing of the disavowal inherent to much of the 90s and 00s paranoid style, however, than the climactic moment in “Pizzagate.” When Edgar Welch entered Washington, DC’s Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor with an AR-15 on December 4, 2016 to “rescue” the victims of a child trafficking ring ostensibly run by Hillary Clinton and her cronies, he showed just how deadly serious the paranoid style had become (Ortiz). Countless mass shootings since—against gay clubbers in Orlando, Jewish worshipers in Pittsburgh, Latinx shoppers in El Paso, Black shoppers in Buffalo, and many others besides—have only reinforced that perception.

At the same time, and only slightly less troubling, the very grounds for paranoia’s alternative appear to be shifting. At the end of his seminal essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” Richard Hofstadter remarks that “one of the most valuable things about history is that it teaches us how things do not happen.” One can surely say as much of personal experience. In the face of claims that the Bush administration brought down the Twin Towers, for example, a logical thinker with at least a modest understanding of world politics would likely ask: if 9/11 was indeed a government-constructed fiction aimed to bring down Saddam Hussein, why were nearly all of the ‘fictional’ hijackers Saudis, and none Iraqis (We 4.16)?

But what if historical understanding is devalued and experience itself ever more unreliable? How does one develop that intuitive sense of “how things do not happen” at a time when political discourse increasingly takes place in mediatic echo chambers, on the left as on the right; when our faith in visual evidence is challenged by the mounting sophistication of AI-enabled deepfakes; and when the privilege of authority itself is undermined, in part through an otherwise salutary questioning of traditional authority’s implicit biases.

In the early 21st-century, in other words, Hofstadter’s corrective to the paranoid style has largely fallen victim to an erosion of that consensual sense of reality or facticity on which it depends, and to the countervailing emergence of specifically tribal realities or facticities. And any contemporary paean to the virtue of Hofstadter’s intuitive sense must, at the very least, wrestle with a style of political decision-making—governance by “gut feeling”—that has landed post-9/11 America in any number of quagmires, beginning with the Second Iraq War.

As outmoded as the concept of wisdom can appear, it is in fact a perfect antidote to the paranoid style of American political culture today. Where the paranoid style sees life as a clear-cut struggle between the forces of good and the forces of evil, wisdom sees any field of social action as both cognitively and ethically complex and the actions of individuals as profoundly shaped by their particular social, cultural, economic, and/or religious contexts. Where the paranoid style flattens out the other, seeing in her only a cog in a (generally evil) machine, wisdom fosters empathic care for the other, a deep-seated sense of social justice, and an overarching concern for the common good. Where the paranoid style flatters what Freud famously called “His Majesty the Ego,” wisdom seeks the good of the community as a whole (150). Where the paranoid style offers a “privileged representational shorthand” for grasping our increasingly ungraspable networks of power, wisdom strives to tease out those networks’ primary nodes and means of control (Jameson 37). (Just days after the fall of Lehman Brothers in 2008, for instance, the Internet was rife with reports that the unfolding financial crisis was the result of machinations by George Soros or (yes) even the Bavarian Illuminati.) Finally, where the paranoid style seeks to capture all the world in a single grand narrative, wisdom practices more humble and nuanced modes of narration and cognition.

Let’s be clear. The world of the paranoid style can be fun, even thrilling. It grants a reader, viewer, politician, or rally attendee a greater sense of self-importance by turning complex struggles into battles of unalloyed good against absolute evil and by placing him or her at the very center of those struggles, often in a savior role. Wisdom’s world is messier, more other-focused and overdetermined, with shades of gray most everywhere one looks. But ultimately, that is the world, in all its chaotic glory.

I miss paranoia, but I opt for wisdom.