No wise liberal has ever thought that liberalism is all of wisdom…. Liberalism isn’t a political theory applied to life. It’s what we know about life applied to a political theory.

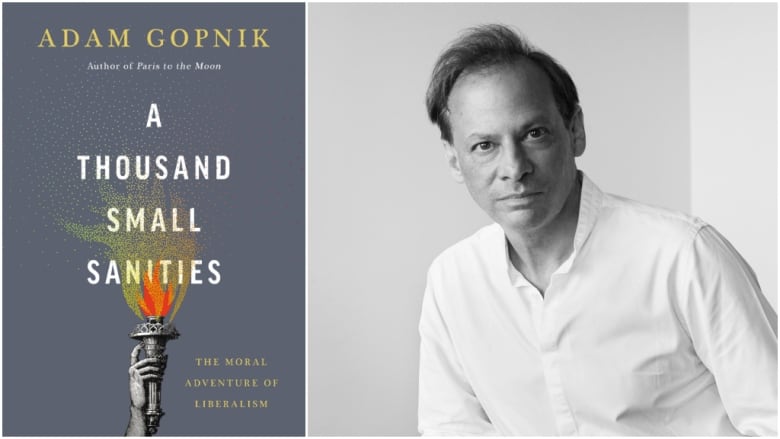

Adam Gopnick, In Praise of Small Sanities

In his work for The New Yorker since 1986, Adam Gopnik has profiled a wide array of (alas, uniformly Western and male) philosophers, writers, and politicians of the early modern and modern eras. A Thousand Small Sanities ties much of this writing together with a focus on liberalism. In the process, it demonstrates how, at its best, philosophical liberalism promotes all five of the markers of wisdom I have been tracking here.

In Gopnik, the insistence on complexity tends primarily to be historical and meliorist, as when he praises reformists for recognizing “that tradition is a very mixed bag of nice things and nasty things, and that we can work together to fix the nasty ones while making the nice ones available to more people” (40). The “larger project of human emancipation,” he writes, depends “on being able to see past categories and types toward actual people and their predicaments” (179). The problem with the traditional Marxist critique of “the bourgeoisie,” for instance, is that the term denotes “an essentialized class with no referents” (178). And for Gopnik: essentialism “is extremism… in its denial of plurality, possibility, ambiguity, double usage, multiple identities” (178).

Rich contextual (and often historical) understanding is critical to the liberal project in that it fosters effective contextual action, typically in a reformist mode. Successful projects of pragmatic reform require deep insight into the many competing interests, values, and beliefs at play as those projects develop.

Throughout his book, most notably in his reading of David Hume and the later Adam Smith, Gopnik praises philosophical liberalism for recognizing “the primacy of sympathy as social cement” (25). Against those who perpetrate the “myth” of a liberalism solely concerned with “individuals and their liberties,” Gopnik tracks historic liberalism’s “rich imagination of common fates and shared values,” arguing that “liberal individualism always emerges from an assumed background of connectedness” (6, 125).

Gopnik was raised in Montreal and often looks to Canada, not the U.S., for signs of a successful liberal order. Rehearsing Canada’s origins as a nation, for example, he argues that nineteenth-century liberal nationalism “was inherently patriotic in the modern sense… supremely preoccupied with building coherent communities across ethnic lines” (126). It follows that a properly liberal conception of civilization does not come from the top down but is built up from “social capital made from small communities” (68). Witness, Gopnik suggests, how community action and community policing combined to create “vicious circles of sympathy” that helped reduce crime in the South Bronx (70f.).

A few pages into A Thousand Small Sanities, Gopnik writes a paean to John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor that nicely encapsulates his argument’s hopeful thrust. Mill and Taylor, he suggests, were not centrists but “radicals of the real, determined to live in the world even as they altered it” (12). Knowing that they were “imperfect, divided people,” armed with “the rueful knowledge of human contradiction that good people always have,” they recognized that all life—from the intimate to the political and social—was “an accommodation of contradictions” (12f.) Compromise, grounded in the recognition that the moral conscience of others may drive them to outcomes different from one’s own, is thus “not a sign of the collapse of one’s moral conscience. It is a sign of its strength” (13).

We will see a good example of this in a later post. Readers of Louise Erdrich’s The Night Watchman will almost inevitably be disappointed when Thomas Wazhashk opts to play to the righteousness of his adversary, Arthur V. Watkins, and seek a postponement of his tribe’s termination, rather than a full reversal of the underlying termination policy. For Patrice, and for our utopian side as readers, the Puerto Rican separatists’ act of firing a gun in the House chamber is more seductive. But it was Thomas’ approach that ultimately leads to a favorable result for his people, not the separatists’.

This brings us to Gopnik’s title and his book’s pertinence to my work. Arguing that liberal reasoning “is an ongoing, surprising, vigilant action,” Gopnik arrives at liberalism’s “one central truth”: that big problems rarely get solved by big ideas, but rather through “the intercession of a thousand small sanities,” which are “usually wiser than one big idea” (227). “No wise liberal,” he writes, “has ever thought that liberalism is all of wisdom…. Liberalism isn’t a political theory applied to life. It’s what we know about life applied to a political theory” (238).

As children, we develop what we know about life through the hearing of stories. As adults, we refine that knowledge in part through the experience of literature, film, drama, and the encounter with more sophisticated stories. Gopnik acknowledges the power of these practices in stating that, because liberalism is “more a way of managing the world than a fixed set of beliefs” and because it is more focused on “personal example” than on ideology, “poets and novelists and painters can be better guides to its truths than political philosophers or pundits” (21).

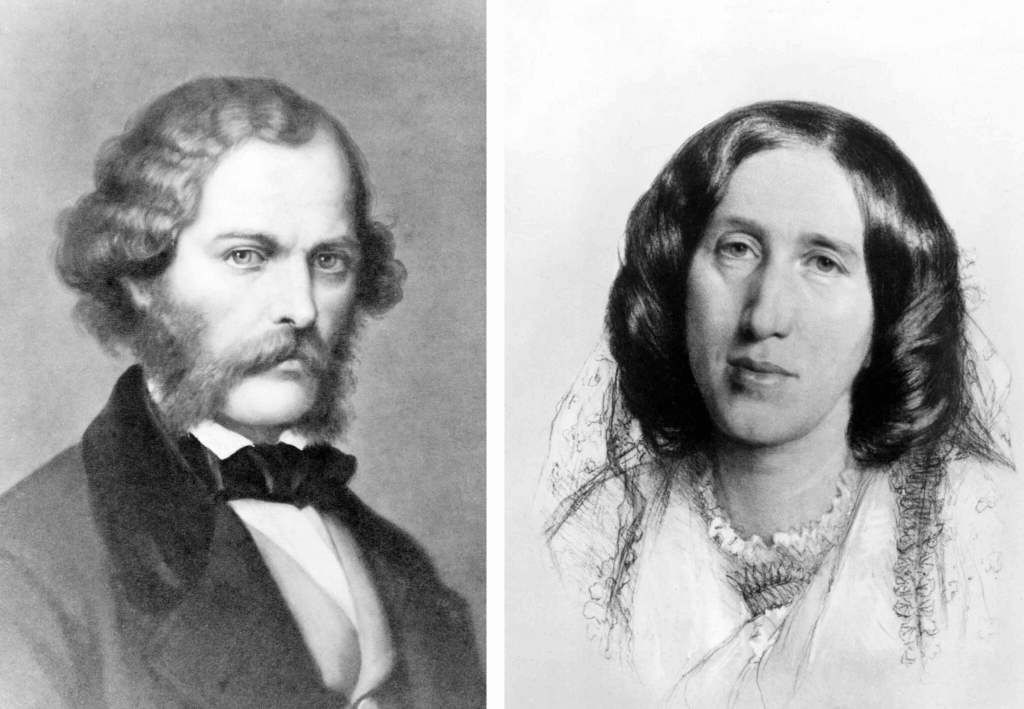

Not surprisingly, one of the personal examples that Gopnik uses to illustrate the power of liberalism prior to its twentieth-century neoliberal turn is the life and work of George Henry Lewes and Mary Ann Evans, a.k.a. George Eliot. Eliot and Lewes, he writes, were “liberals of process” who, as strong readers of Darwin, were fully attuned not just to the “unpredictable complexity of causes,” but also to the “eternal possibility of change” (52, 62).

Photo: Everett Collection/Bridgeman Images

It may well be that the human mind is wired to prefer magical utopian solutions over the ceaseless but ever-renewed effort of making important but incremental change toward a more just and equitable world. What is surely true is that the liberal project as Gopnik understands it is under particularly sustained pressure today, undermined as it is by autocratic leaders who promise the return to a mythic greatness, by a media sphere that rewards simplistic invective over patient analysis, and by the rise of populist anti-intellectualism, with its growing distrust of informed opinion and disdain for fact-based reasoning. We live, as Gopnik would put it, in an age of unicorns, in which big ideas consistently seem to outshine small sanities. Like Gopnik, I believe that art—and literary work in particular—helps to refocus our attention on the small things in life that truly matter and that push us to go beyond our imperfect natures, to make the world a more just and empathic place.