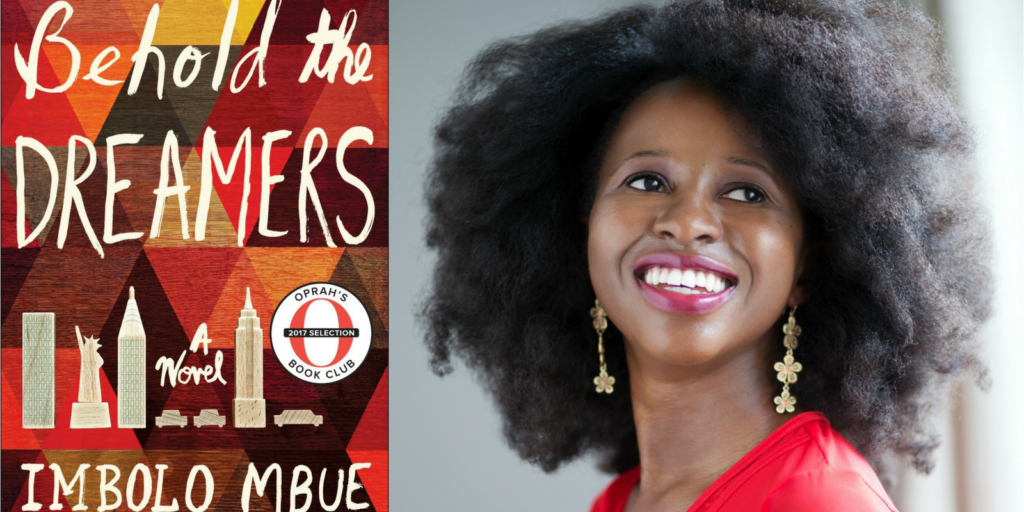

But then along comes “Behold the Dreamers,” a debut novel by a young woman from Cameroon that illuminates the immigrant experience in America with the tenderhearted wisdom so lacking in our political discourse.

Ron Charles, The Washington Post

This is the second in a series. You’ll find the series’ conceptual framework here.

Imbolo Mbue’s debut novel, Behold the Dreamers, recounts the efforts of the Jonga family—wife Neni, husband Jende, and son Liomi—to leave behind their native Cameroon and make a new life for themselves in New York City. Set at the time of the 2008 financial crisis, the novel juxtaposes the Jongas’ struggles with those of the Edwards family, for whom Jende works as a chauffeur—until both families find their worlds turned upside down with the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The novel ends with the Jongas’ bittersweet return to Cameroon and with husband Clark Edwards leaving New York for the D.C. suburbs, following the drug- and alcohol-induced death of his wife, Cindy.

In a review of Mbue’s novel entitled, “’Behold the Dreamers’: The One Novel Donald Trump Should Read Now,” Washington Post critic Ron Charles rightly speaks of the book as illuminating “the immigrant experience in America with the tenderhearted wisdom so lacking in our political discourse” today. Much of the novel’s magic lies in the gentle—indeed, “tenderhearted”—irony with which Mbue treats Jende and Neni’s illusions and naïveté about life in the U.S. We are tempted to chuckle, but ultimately catch ourselves, when Jende shows up for his interview with Clark in a “green double-breasted pinstripe suit”; when he tells Neni “maybe it was best to live in peaceful American cities, like New York City”; when a family friend suggests shopping at a “[f]ine white people store lika Target”; or when Jende mistakes Enron for a “person” and becomes flummoxed by the phrase, “They cooked their books” (3, 28, 32, 50f.). Far more so than his wife, whose investment in the idea of a new life in the U.S. proves deeper in the end, Jende gives voice to a tautological exceptionalism much like that which fuels so much nativist rhetoric today. In telling Clark why he chose to leave a Cameroonian hometown “made of magic,” Jende explains that “America is America…. Everyone wants to come to America” (38f.). “Truly,” he later suggests, “there was nothing much to see outside America” (72).

As the novel unfolds, Mbue increasingly invites the reader to be brought up short by the Jongas’ blindness to the ills endemic to American society. On a nighttime stroll to Columbus Circle, Neni notices that “most people on the street were walking with someone who looked like them,” only to turn this perception of social segregation into a net positive for the city: As the novel unfolds, Mbue increasingly invites the reader to be brought up short by the Jongas’ blindness to the ills endemic to American society. On a nighttime stroll to Columbus Circle, Neni notices that “most people on the street were walking with someone who looked like them,” only to turn this perception of social segregation into a net positive for the city:

Even in New York City, even in a place of many nations and cultures, men and women, young and old, rich and poor, preferred their kind when it came to those they kept closest…. That was what made New York so wonderful: It had a world for everyone. (95)

Later, as Jende reflects on the Old Testament parallels to the “unprecedented plague” that was the financial crisis, he reasons that “the Egyptians had been cursed by their own wickedness…. They had chosen riches over righteousness, rapaciousness over justice. The Americans had done no such thing” (185).

Such illusions die hard, but die they eventually do. One of Behold’s narrative arcs runs from illusions, gently and empathically portrayed, to disillusionment—the spur to a more profound form of empathy on the reader’s part. Mbue has spoken of discovering, on her arrival, “that widespread poverty exists in America” and of the “sense of failure” and “shame” that comes from being poor in New York City (390). In the wake of the financial crisis, the heretofore hopeful Jende comes to recognize that, “[i]n America today, having documents is not enough” and that “even some Americans are suffering” (307). Reflecting on how none of Cindy Edwards’ family and friends intervened to stop her downward slide into addiction, Jende asks: “What kind of country is this?” (287). Finally, as he struggles to persuade Neni to return to Cameroon and give up her dream of becoming a pharmacist in America, Jende rants (without the least bit of self-irony) “about how she had been sold the stupid nonsense about America being the greatest country in the world” when it is “full of lies and people that like to hear lies” (332).

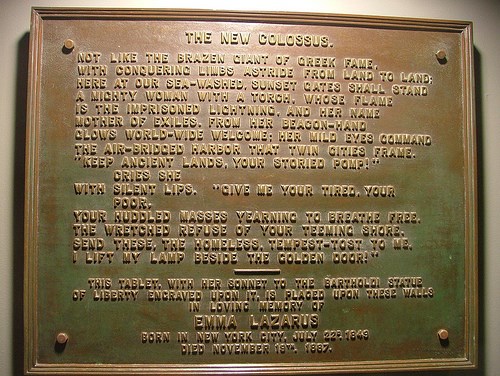

Hovering over Behold the Dreamers is a theme announced in the title of a Wall Street Journal article that Jende spies during his interview with Clark in the novel’s opening scene: “Barack Obama and the Dream of a Color-Blind America” (5). Obama’s candidacy, then his election and inauguration, long serve for Jende and his fellow Africans as a testament to the promise of America, and not just from the hope that he or Hillary Clinton might “one day… give everyone papers” (40, 74). Mbue’s title clearly asks to be understood in the context of her remark that “both the Obamas and the Jongas were dreamers—different kinds of dreamers, but still dreamers” (391). If the novel never directly announces the collapse of the dream of a color-blind America, it doesn’t need to. In her good-bye sermon on the Jonga family’s plight, Neni’s friend Natasha says that they “came to America to stay but we won’t let them… because we as a country have forgotten how to welcome all kinds of strangers to our home” (365).

My reading to this point has focused primarily on the two elements of wisdom most central to the novel of migration—an appreciation of cultural difference and empathy for the other. I would argue, however, that Behold the Dreamers is no less remarkable in the way it respects and fosters a certain ethical complexity. Reflecting on the process of writing her novel, Mbue has observed that

it was a long journey for me to develop empathy for Clark and Cindy Edwards…. Writing this novel was a lesson in empathy…. [T]o tell this story honestly and completely, I had to learn to see them as humans—imperfect humans, yes, but still humans like the rest of us. (392)

Mbue could easily have cast Clark Edwards, with his philandering disregard for his wife and his love for “the game,” as the stereotypical embodiment of Wall Street heartlessness pre-2008 (100). Yet she chooses to make Clark the spokesperson within Lehman for a more humane and transparent approach to the subprime mortgage crisis. However badly Clark may wish that there were “more conscience on the Street,” he recognizes that he remains very much a “part of it” (182). By novel’s end, Clark has said goodbye to Wall Street and “made his life revolve around family” in a way that Jende never quite manages to do (340f.). Indeed, the complexity of Mbue’s characterization of Clark is such that, to quote Ron Charles, there is no villain in Behold beyond “the vast bureaucracy designed to wall off the American Dream from outsiders.”

Nothing better illustrates Mbue’s commitment to tell her story “honestly and completely,” while illuminating real life conundrums, than her depiction of Neni’s struggles with traditional Cameroonian gender roles. Time and again, Jende conspicuously thinks of life decisions affecting his wife and child as his alone: “Neni had her dreams of a condo in Yonkers or New Rochelle because she didn’t want to leave her friends… but [Jende] knew he would leave behind the city and its hopeless predicaments” (82).

When Neni becomes pregnant with her second child, Jende “informs” her, without discussion, that she’ll be dropping out of school for two semesters and staying home after the baby arrives (171). “Eventually, shamefully,” she decides to defer to Jende’s “wisdom”, rationalizing that decision by reasoning that “few women (rich women included) had the privilege of being married to an overly protective man” (173). But it is Fatou who best illustrates the plight of traditional Cameroonian women when she derives the following moral from the story of a cousin whose husband beat her for having a beer in public with another man: “She learn lesson, marriage continue, everybody happy” (80).

Neni’s desire to stay in America—where women are said to “tell their men what they want and the men do it, because they say happy wife, happy life”—clearly grows out of her desire to be “in control of her own life” (199, 63). Her decision to shake down Cindy Edwards with a photo she had taken of Cindy in a drunken stupor—”drool running down her chin, her upper body splayed against the headboard”—reads like a watershed moment, inasmuch as the initially furious Jende comes finally to recognize that he has married “a strong woman” (266, 273).

By novel’s end, however, Neni has conspicuously renounced her budding independence. Having told herself she would never leave America, she googles for help on how to convince a husband and finds “no advice relevant to her situation” (315). After Jende slaps her and calls her “a selfish woman who would be happy to see her husband die in pain all so she could live in New York,” Neni rightly remarks: “America has beaten you and you don’t know what to do and now you thinking hitting me will make it better”—before inviting him to hit her again (334). Neni conspicuously chooses not to file charges against Jende, as “wives in America did when their husbands beat them,” and then forgives him (336). The chapter closes with a tearful Neni looking at Jende and saying “how glad she was that his ordeal might soon be over” (337; my emphasis).

Neni’s reversion to the traditional wifely role cannot help but be profoundly dissatisfying to most of Mbue’s readers. One metric of Behold’s wisdom, however, is how deeply Mbue draws us into complex, culturally determined quandaries like this one, inviting us to empathize with characters struggling to find their truth in a world that is, as President Obama put it, “complicated and full of grays.” Behold the Dreamers raises more questions than it provides answers to, inviting us in scene after scene to reflect on the situational rightness, or not, of its characters’ judgments and actions in the world. It is thus fitting that the novel ends pensively, with a question from son Liomi on the family’s arrival back in the Cameroonian town of Limbe: “The boy opened his eyes and said, “Home?” (382).