Photo: Sri Lanka Guardian

Wise judgment is attuned to cognitive complexities in the world and to the ways in which historical and cultural contexts inform diverse systems of value. Whatever their domain of action, wise practitioners evince high degrees of intellectual humility and empathy, together with a thoroughgoing commitment to fostering the well-being of both one’s self and one’s community.

This blog examines how the reading of literature, broadly construed, might serve to combat the many drivers of unwisdom in our twenty-first century world.

The past 15 years have seen the emergence of several strong critical studies on how the nineteenth-century novel, especially works by Tolstoy and Austen, has served to foster readerly wisdom. I am thinking here of Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro’s Cents and Sensibility, Andrew Kaufman’s Give War and Peace a Chance, and William Deresiewicz’s A Jane Austen Education. Morson and Schapiro capture the main thrust of this work in arguing that the great realist novels—works by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Austen, George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë, Wharton, Henry James, and others—offer “rich cases for ethical reflection” that involve the reader in a “practice of empathy,” as the result of which readers “acquire the wisdom to appreciate real people in all their complexity” (10-13). As readers, we follow the social and ethical development of complex characters as they negotiate a multifaceted and uncertain world, always attuned to their mixed motivations, missteps, misreadings, self-destructive tendencies, or moments of folly. We are privy to their changing conceptions of a life well lived, for themselves and for others, and to the actions that evolve therefrom (Eliot’s Dorothea Brooke is a classic example). Humility comes into play as we participate in our characters’ attempts to master a confounding world and to overcome their initial misjudgments. (Tolstoy’s War and Peace is paradigmatic of the first approach, Austen’s Pride and Prejudice of the second.) And because we are typically granted insight into the thoughts and motivations of multiple characters, we see how conflicts arise from divergent social experiences and value systems, and how such conflicts might ultimately be resolved.

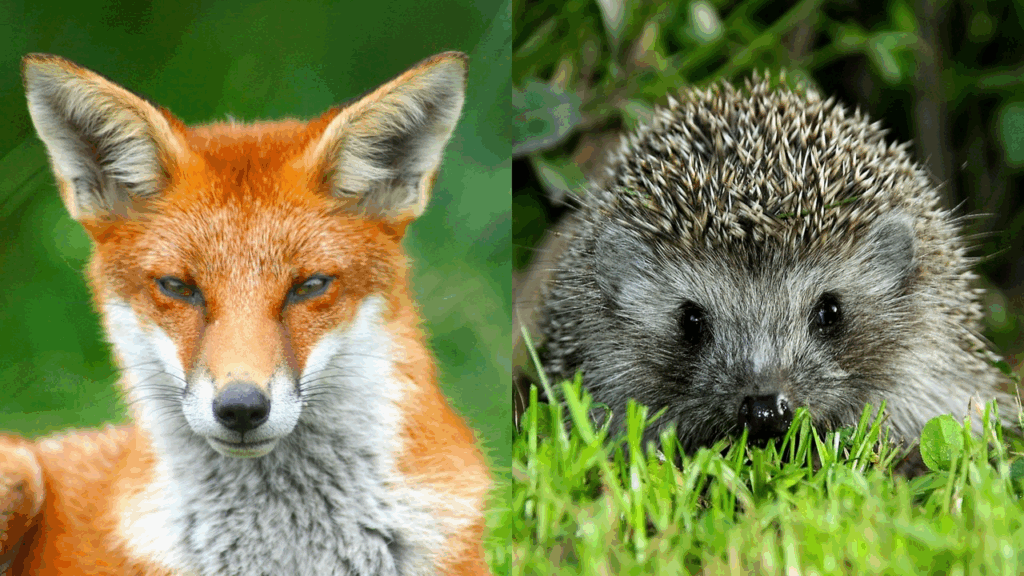

Morson and Schapiro nicely capture what is at stake in the reading of these novels in referencing Isaiah Berlin’s well-known distinction between hedgehogs and foxes.

Whereas hedgehogs (e.g., theorists, economic or otherwise) seek to “relate everything to… a single, universal organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance,” foxes “lead lives, perform acts and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal… seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves” (Berlin 2). Or as Morson and Schapiro put it: whereas “hedgehogs see complexity as an illusion, concealing an underlying simplicity, foxes see just the opposite” (58). “Literature by its very nature,” they conclude, “is foxy” (63).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

That certain psychologically rich and generally European realist novels function as schools for a certain wisdom is, by now, a familiar argument. What one finds a good deal less of in the critical arena is an analysis of how wisdom is promulgated in literary production of the late 20th– and early 21st-centuries by a rich range of more culturally and geographically diverse authors. To focus principally on the nineteenth-century novel—or on the much older wisdom texts of philosophy and religion—is, I would argue, to risk missing the variety and dynamism of wisdoms today.

In writing this blog, I have drawn heavily on the growing body of recent psychological and neuroscientific work on the concept of wisdom, much of it inspired by Aristotle’s conception of phronesis or “practical wisdom.” As useful as it is, however, much of psychology’s wisdom work is constrained by the limitations of the experimental model at its core: too focused on individuals rather than collectives, too blind to the influence of social and cultural contexts, and too attentive to what can easily be measured over a short period of time. As a body of work, moreover, it often suffers from definitional overload. Because I strongly agree with Alisdair MacIntyre’s characterization of narrative as “the basic and essential genre for the characterization of human actions,” I much prefer a “narrative” approach to understanding experience over what Jerone Bruner calls its “logico-scientific/paradigmatic (categorical)” counterpart (MacIntyre 208; Bruner, qtd. in Ferrari and Kim 417). Focusing on narratives—whether fictional or autobiographical—allows one to foreground the acquisition of wisdom as a struggle, a never-ending process that unfolds over time, both for the narrative’s subject and for the reader or listener. That said, this body of psychological work, and its philosophical analogue, are vital in proofing the assumptions that literary scholars (including me) can be too quick to make. To take an example I will discuss later, there is an important (and maddingly inconclusive) body of studies around the claim, as Morson and Schapiro phrase it, that “[e]ndlessly repeated, [the reader’s] experiencing of another person from within teaches us empathy by making it a habit” (230).

Photo: TeleRead

Three further caveats in anticipation of “A. Ham in the Age of Trump,” the short piece that was in many ways the genesis of this project. First, reading literature is an opportunity for wisdom, but it is hardly a guarantee. Much as we would like to think otherwise, those of us who populate academic departments of literature or review novels, films, and plays for a living have no particular lock on wisdom.

Second, as will become apparent in the course of this study, the wisest contemporary texts are often those that neither speak of wisdom explicitly nor present themselves as guides for future experience. Typically, contemporary “wisdom literature”—to highjack a phrase historically applied to highly canonical texts, including the wisdom books of the Old Testament—neither revolves around a character’s quest for greater wisdom nor addresses its reader in the mode of a ‘how to’. Indeed, the wisest texts in the posts that follow are typically quite complex, and thus require of the reader a cognitive struggle much like that inherent to the struggle for wisdom itself. Wisdom in and through these texts, in other words, is not a goal but a by-product, and the fruit of appreciable effort.

Finally, “wisdom” is what Claude Lévi-Strauss famously termed a “floating signifier.” Like “freedom” or “democracy”, “wisdom” points to a concept with no stable referent, and thus remains open to radically different meanings in different discursive contexts. I will have occasion to unpack wisdom’s role as grounds for dissensus in several of the readings below.

For my purposes here, however, it is important to specify from the outset what exactly I understand by “wisdom”—namely, a capacity for sound judgment with a view to pragmatic action. Wise judgment is attuned to cognitive complexities in the world and to the ways in which historical and cultural contexts inform diverse systems of value. Whatever their domain of action, wise practitioners evince high degrees of intellectual humility and empathy, together with a thoroughgoing commitment to fostering the well-being of both one’s self and one’s community. Many of these values having important philosophical, political theoretical, and religious antecedents dating back millennia. Still, this conception of “wisdom” is very much a construct of the cultures from which I write, albeit a construct that I will happily argue for.