Photo: Nasty Women Writers

It is only by seeing ourselves as fundamentally other—the contingent product of a culture that has no particular monopoly on truth—that we can come into our wisest possible, most “utterly human” selves.

At first blush, my choice of a work of science fiction to end this series on empathy and cultural dislocation might seem strange. We have all experienced far too many science fiction narratives that, like their imperialist or colonialist forebears, reduce the alien being to an Other to be vanquished and subdued in the interest of furthering a dominant culture. Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels, however, deliberately and consistently break that mold. In a short piece from 1996, “Which Side Am I On, Anyway?”, Le Guin reflects on her parents’ anthropological fieldwork “among the wrecks of [Native American] cultures, the ruin of languages, the shards of infinite diversity swept aside by a monoculture,” then goes on to write:

innate or acquired, an ability to learn an unfamiliar meaning, and an inability to limit significance to one side of the frontier, have shaped my writing. Americans have considered the future as a frontier, an empty place to be annexed and filled. In my science-fiction works the future is already full; it is very much older and larger than our present; and we are aliens in it. (27f.)

Le Guin’s 1969 masterwork, The Left Hand of Darkness, is a case study in how the representatives of mutually alien cultures—and, by extension, we as readers—work to overcome the all-too-human tendency to limit meaning “to one side of the frontier” and, in the process, to grow in wisdom. In its foregrounding of the struggle for empathy, its attention to ethical complexities, its highlighting of the determinative power of culture context, and its author’s fundamental humility, Le Guin’s novel is a fully realized piece of wisdom work.

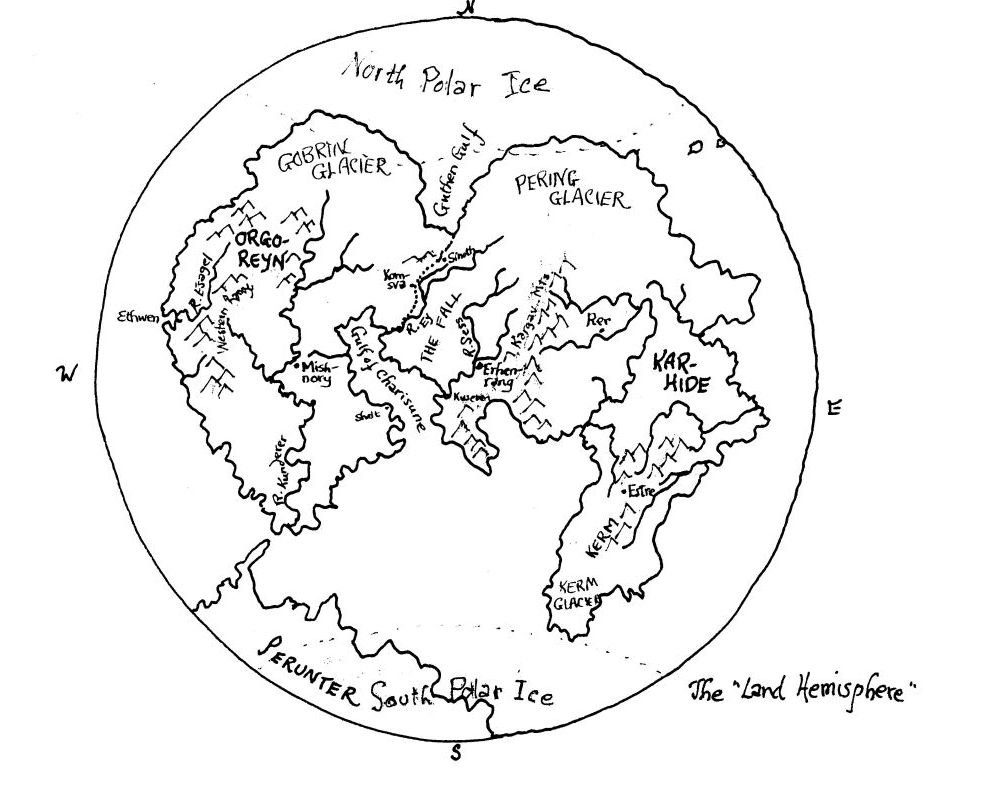

In its simplest form, Left Hand’s plot tracks the mission of a young Genly Ai to the far-flung planet Gethen—nicknamed Winter for its frigid climate—in an attempt to persuade the Gethenian nations to join a league of 83 other inhabited planets, the Ekumen of Known Worlds.

Photo: Ursula K. Le Guin Literary Trust

In the nation of Karhide, where the story begins, Genly meets, but comes to distrust, Therem Harth rem ir Estraven, Karhide’s prime minister or so-called King’s Ear. When Karhide’s mad king Argaven banishes Estraven upon penalty of death for his advocacy of union with the Ekumen and for causing the king to lose face in a border dispute with the neighboring nation of Orgoreyn, Estraven takes refuge in Orgoreyn. Finding Karhide unreceptive to his overtures, Genly in turn travels to Orgoreyn in the hope of fulfilling his mission but, suspected of being the agent of a Karhide “hoax”, is imprisoned in a remote Voluntary Farm (160). After a daring Estraven frees Genly from his captivity, the pair undertake a treacherous, months-long journey back to Karhide over the Gobrin ice sheet.

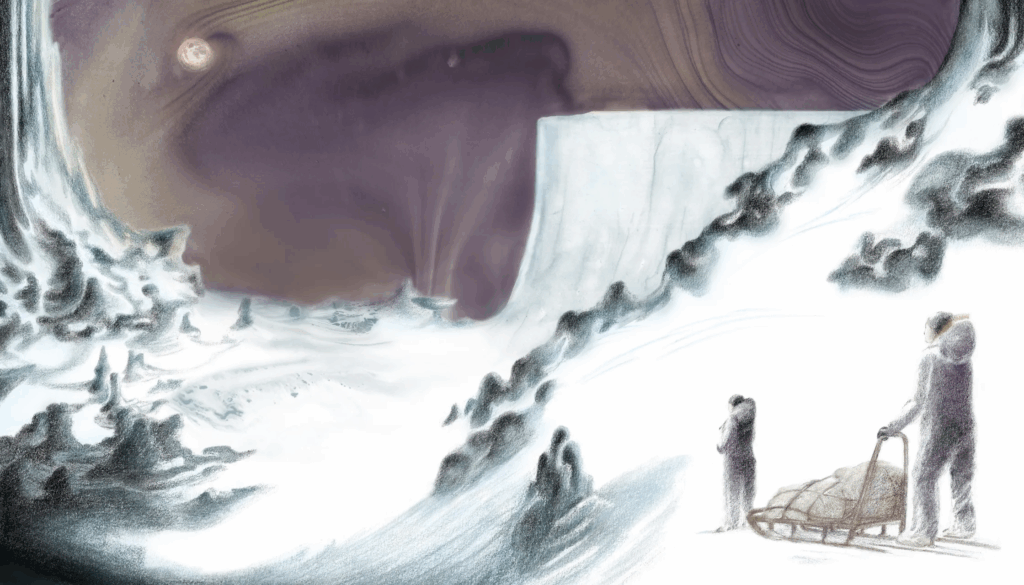

Photo: Jacqueline Tam, The New Yorker

Once again in Karhide, Estraven is betrayed and shot attempting to escape. Genly, however, persuades Argaven to join the Ekumen and, by novel’s end, has been granted the title Envoy Plenipotentiary of the Ekumen.

Summarized in this way, Left Hand’s plot hardly seems remarkable. What sets the novel apart and lays the foundation for wisdom is encapsulated in three fundamental difficulties that the reader quickly faces: the novel’s complex narrative structure, its grounding of Gethenian actions in a strikingly alien set of cultural values, and its foregrounding of an equally unfamiliar form of sexual embodiment. Let me take these difficulties in turn.

The Left Hand of Darkness’s narrative structure is nothing if not disorienting. The novel’s first chapter, narrated in the first person, is ostensibly drawn from a report that Genly Ai filed on his activities on Gethen, as are nine of the 19 chapters that follow. Chapter Six and three others, likewise in the first person, are drawn from Estraven’s journal. In the midst of these, beginning with Chapter Two, Le Guin gives us various Gethenian hearth-tales, myths, and legends, as well as field notes on Gethenian sexuality from an earlier Ekumenical Investigator. As the novel proceeds, especially in the ice sheet chapters, we are treated to an insightful and relatively easy-to-follow counterpoint between Genly’s and Estraven’s versions of the same events. And in time, the insertion of expository prose on Gethenian cultural, sexual, and religious life comes to feel less jarring alongside the twinned first-person narratives. But Le Guin clearly wants to unsettle her readers by showing that no first-person narrator can begin to capture the whole of her story.

Lest we be inclined to miss this point, Le Guin has Genly begin his report as follows:

I’ll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination….

The story is not all mine, nor told by me alone. Indeed I am not sure whose story it is; you can judge better. But it is all one, and if at moments the facts seem to alter with an altered voice, why then you can choose the fact you like best; yet none of them is false, and it is all one story. (1)

As readers, we expect first person reports, perhaps especially from an envoy from our home planet of Terra, to reliably communicate the facts of (in this case) his mission. But Le Guin undercuts this expectation from the outset, undermining our confidence in what we read and setting the stage for a narrative told in a “bewildering array of voices”—several personal but others broadly cultural—where the onus for the ultimate determination of meaning lies squarely with the reader (Cornell 322). In so doing, she explicitly unsettles the traditional novelistic contract, in which the reader cedes power to an author and narrator in return for the pleasure of a coherent story.

The two primary sources of those facts from among which Le Guin, through Genly, invites us to choose are those presented by Estraven and Genly himself. Curiously, the novel pronounces both to be wise, but complexly so, inasmuch as each evinces serious limitations of judgment or perspective. Reflecting on a speech that Genly had given to the leaders of Orgoreyn, Estraven writes:

There is an innocence in him that I have found merely foreign and foolish; yet in another moment that seeming innocence reveals a discipline of knowledge and a largeness of purpose that awes me. Through him speaks a shrewd and magnanimous people, a people who have woven together into one wisdom a profound, old, terrible, and unimaginably various experience of life. But he himself is young: impatient, inexperienced. He stands higher than we stand, seeing wider, but he is himself only the height of a man. (168)

Genly benefits from a great store of collective wisdom as the representative of a people that, having lived through a disastrous “Age of Enemy,” “outgrew nations centuries ago” and no longer governs by “fear of the other” (146f., 20). His is a “league or union of worlds” that relies on the “motives of communication and cooperation,” not colonialization, and for which “[p]ower has become so subtle and complex a thing… that only a subtle mind can watch it work” (146f., 7). But, for most of the novel, Genly’s personal judgment is (as we will see in a moment) seriously flawed.

By contrast, Estraven is (in the words of an Orgoreyn leader) “shrewdly mad, wisely mad” (92). Although he repeatedly misunderstands Genly, Estraven is blessed with exceptional intuition, “the power of seeing (if only for a flash) everything at once: seeing whole” (219). Above all, Estraven exemplifies the specific wisdom of the Handdara Foretellers, which Genly aptly characterizes (in what otherwise seems to be a throwaway comment) as “paradox developed into a way of life” (271). Arguing that “[t]o oppose something is to maintain it,” such that “[t]o be an atheist is to maintain God,” Estraven becomes the primary driver of the novel’s plot to the extent that he recognizes that “Orgoreyn and Karhide both must stop following the road they’re on…. They must go somewhere else, and break the circle”—specifically by aligning themselves with the Ekumen (163f.).

Photo: The Rogue Theatre

What then stands in the way of Estraven’s helping Genly to accomplish his mission? The first obstacle—and the second of the readerly difficulties I referenced above—is the Gethenian practice of shifgrethor, which Genly describes early on as “prestige, face, place, the pride relationship, the untranslatable and all-important principle of social authority in Karhide and all civilizations of Gethen” (14). Later, he will admit: “I’ve never even really understood the meaning of the word” (266). The problem for Genly, and for most of us as Terran readers, is that shifgrethor seems to mean two quite different things. On the one hand, it names what Le Guin herself has called “a socially approved form of aggression… a conflict without physical violence, involving one-upsmanship, the saving and losing of face—conflict ritualized, stylized, controlled” (“Redux” 3). It is because Gethenians have developed this “sublimation” of physical violence that they have thus far managed to avoid the “mass violence” that is war (108, “Redux” 3). On the other hand, shifgrethor tends to preclude “giving, or accepting, either advice or blame” (213).

Following a meeting with Genly in Orgoreyn, for instance, Estraven speaks of Genly’s not recognizing that he had insulted him “deliberately” (161). I dare say most readers are surprised at this. Estraven had indeed warned Genly—correctly, as it turns out—against his becoming “the tool of a faction” in Orgoreyn’s governance structure (141). But far from taking Estraven’s insult as it was intended, Genly accepts the advice and is only troubled by how the conversation had broken his “mood of peaceful self-congratulation” (142). Given how desperately Genly needs Estraven as a sounding board to advance his mission, Estraven clearly takes a step forward when he comes to ask: “Is it possible that all along in Ehrenrang [Karhide’s capital] he was seeking my advice, not knowing how to tell me that he sought it?” (162).

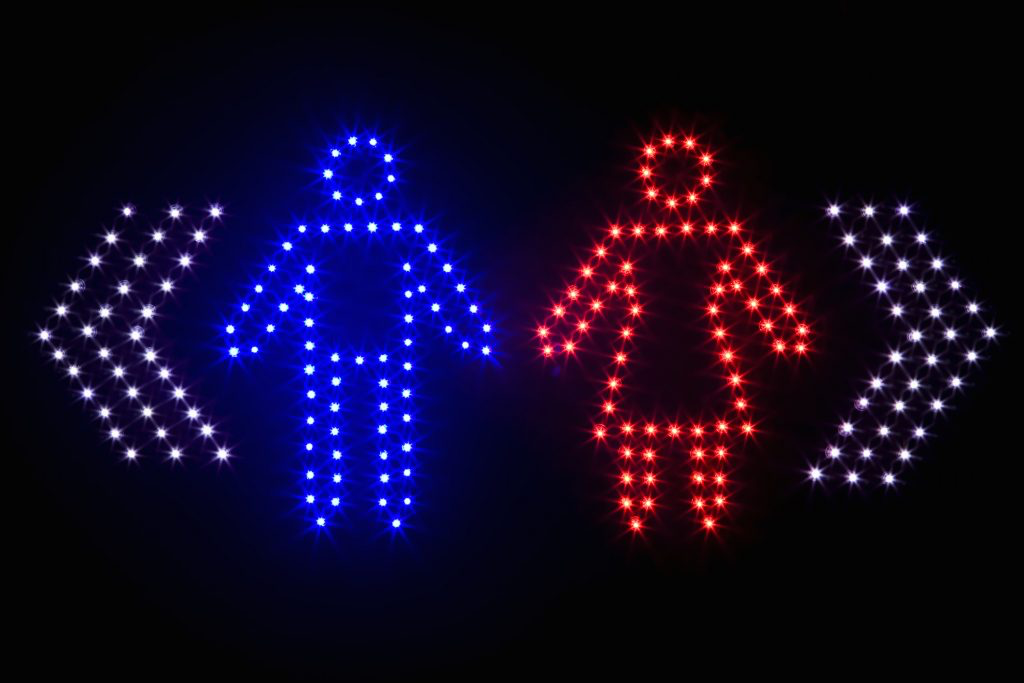

The second major form of cultural opacity in The Left Hand of Darkness, and the third and last of the readerly difficulties, involves the aspect of Le Guin’s “thought experiment” that most readers have tended to focus on—namely, her portrayal of Gethenians as ambisexual.

For roughly 5/6 of the lunar month, all Gethenians exist in a state of sexual inactivity called somer. In the remaining days, they experience an intense estrus cycle known as kemmer. Once in kemmer, they can take on either the male and female roles in the act of coupling, such that all can in time be both mothers and fathers. All child-rearing, however, is done by the collective. The result is a society with “no division of humanity into strong and weak halves,” “no unconsenting sex, no rape,” and “no psycho-sexual relationships” with a mother or father (100). On Gethen, we are told, “no one is quite so thoroughly ‘tied down’… as women, elsewhere, are likely to be—psychologically or physically” nor “quite so free as a free male anywhere else” (100). At the same time, the “structure of [Gethenian] societies, the management of their industry, agriculture, commerce, the size of their settlements, the subjects of their stories, everything is shaped to fit the somer-kemmer cycle” (99).

To the Gethenian, Genly AI is a “Pervert,” a “sexual deviant”—stuck as he is in his masculinity and subject to a constant and “strange low-grade sort of desire” (196, 170, 250). For his part, Genly consistently attempts to force the Gethenian “into those categories [man and woman] so irrelevant to his nature and so essential to my own” (12). The culture shock he experiences around concepts such as shifgrethor, he writes, “was nothing much compared to the biological shock I suffered as a human male among human beings who were, five-sixths of the time, hermaphroditic neuters” (50).

From the novel’s opening pages, Le Guin makes it clear that her central narrator is an outright misogynist. Indeed, misogyny would appear to be the primary reason Genly mistrusts Estraven for well over half the novel. Annoyed by Estraven’s “sense of effeminate intrigue” and finding his motives “forever obscure,” Genly perceives Estraven to be “faithless”, asking himself: “Was it in fact perhaps this soft supple femininity that I disliked and distrusted in him?” (12). “Even in a bisexual society,” he goes on to remark, “the politician is very often something less than an integral man” (15).

I have spoken of the ways in which both Mbue’s and Nguyen’s works draw their readers into humbling traps. Le Guin does much the same in revealing that Genly, whom late-60s readers of sci fi likely assumed to be white, is in fact darker of complexion than his Gethenian hosts. But the most telling trap in Left Hand occurs in Chapter Seven, “The Question of Sex,” comprising the field notes from the first Ekumenical landing party on Gethen. Because English lacks the “human pronoun” that Karhiders use to designate persons in somer, the investigator writes, “I must say ‘he’…” because the masculine pronoun “is less defined, less specific, than the neuter or the feminine,” but that pronoun “leads me to forget that the Karhider I am with is not a man but a manwoman” (101). On Winter, the investigator concludes: “One is respected and judged only as a human being. It is an appalling experience” (101). Only in the report’s final paragraph does the investigator reveal herself to be “a woman of peaceful Chiffewar” who, we presume, “wants her femininity appreciated” (103).

Having spent the bulk of the novel “locked in [his] virility: no friend to Therem Harth [Estraven], or any of his race,” Genly only begins to see Estraven “as he was” during their tortuous journey together on the Gobrin ice sheet (229, 216). Galled by what he initially takes to be Estraven’s “patronizing” in assuming that he, Genly, was sick and unable to pull his usual weight, Genly comes to realize that Estraven

had not meant to patronize. He had thought me sick, and sick men take orders. He was frank, and expected a reciprocal frankness that I might not be able to supply. He, after all, had no standards of manliness, of virility, to complicate his pride.

On the other hand, if he could lower all his standards of shifgrethor, as I realized he had done with me, perhaps I could dispense with the more competitive elements of my masculine self-respect, which he certainly understood as little as I understood shifgrethor. (234)

Genly’s and Estraven’s progress toward mutual understanding reaches its apogee when Estraven goes into kemmer, in a series of conversations told first from Estraven’s point of view, then from Genly’s. After Genly evokes the “cults of dynamic, aggressive, ecology-breaking cultures” on other worlds, implicitly including his home planet of Terra, Estraven recites a Handdara lyric, Tormer’s Lay, that both exemplifies the Handdara ideals of wholeness and balance and gives the novel its title: “Light is the left hand of darkness / and darkness the right hand of light. / Two are one, life and death, lying/ together like lovers in kemmer, / like hands joined together, / like the end and the way” (252).

Where other, more technologically advanced worlds practice a dualism grounded in mastery and the pursuit of exploitative ends, the Handdara promulgate a dualism of wholeness and balance that privileges the way. Genly makes explicit the specifically Taoist resonances of this version of Handdara wisdom, and signals a fitting end to his masculinist protest, when he shows Estraven the Taoist symbol for yin and yang, saying: “It is yourself, Therem. Both and one” (287).

Photo: Vanessa Lemen, Both and One

When it is Genly’s turn to recount these conversations on the ice, he speaks of finally seeing Estraven in kemmer “as a woman as well as a man” and recognizes that Estraven was “the only one who had entirely accepted me as a human being… [and] demanded of me an equal degree of recognition, of acceptance” (267). It was “from that sexual tension between us, admitted now and understood, but not assuaged, that the great and sudden assurance of friendship rose…. [which] might as well be called, now as later, love…. For us to meet sexually would be for us to meet once more as aliens” (267).

Again seeking Terran analogues for an experience that transcends his cultural frame, Genly evokes Martin Buber’s conception of “I and Thou” to name a oneness that goes “even wider than sex” (252). The Ekumen’s decision to send him to Gethen alone was “[n]ot political, not pragmatic, but mystical,” he later suggests, to the extent the relationship it fosters is “[n]ot We and They; not I and It; but I and Thou” (279). “Alone, I cannot change your world. But I can be changed by it” (279).

Le Guin wrote The Left Hand of Darkness in the late 60s, a time when it was still common to consider the pronouns he/him/his as generic, “less defined, less specific, than the neuter or the feminine” (101). Not surprisingly, many readers have objected to her reliance on he/him/his to refer to the ambisexual Gethenians. With a generosity typical of literary theoretical work around the turn of the last century, several of Le Guin’s best readers have sought to move beyond this controversy by arguing that the text somehow transcends it. Christine Cornell would caution us against viewing Genly’s masculinist perspective, and by extension the novel’s, “from a detached distance, confident in our own superiority,” inasmuch as that practice “duplicates Genly’s initial treatment of Estraven in particular, and Gethen as a whole” (324). John Pennington argues that the novel’s use of traditional gender categories so as to “expose or escape patriarchy” replicates science fiction’s “inherent contradiction”: the use of “common language and largely conventional narrative structures” to “play the game of the impossible” (351f.). At the same time, Pennington contends, Left Hand “asks that both male and female readers become resisting readers who must identify against their gendered selves and critique those stereotypes” (353).

I find each of these contentions persuasive to a point. But it is important to recognize that readers will of necessity read differently as a result of their gender positionalities and that Le Guin’s thought experiment remains, in her own word, “messy” (“Redux” 3).

Photo: Getty Images

In 1976, Le Guin sought to address the controversies around her novel in a piece entitled, “Is Gender Necessary?” Eleven years later, she republished the piece as “Is Gender Necessary? Redux,” with intercalated comments in italics that reflect both an evolution in her views and a desire to move beyond what she called the “defensive” and “resentful” tone of the original essay (2). What is striking about both versions is the seriousness and care with which Le Guin engages the critics of her (otherwise remarkably successful) novel. Having in 1976 tried to justify her use of he/him/his to refer to the Gethenians out of a refusal to “mangle English by inventing a pronoun for ‘he/she’,” she would write this in 1987: “I still dislike invented pronouns, but I now dislike them less than the so-called generic pronoun he/him/his, which does in fact exclude women from discourse; and which was an invention of male grammarians” (6). Rather than suggesting the pitfalls of reading the text from a position of detachment or arguing that it invites all of us to become resisting readers, Le Guin humbly—and I would argue, wisely—recognizes shortcomings in the novel still more fundamental than the vexed question of pronouns. Here she is in 1976:

The pronouns wouldn’t matter at all if I had been cleverer at showing the “female” component of the Gethenian characters in action…. This is a real flaw in the book, and I can only be very grateful to those readers, men and women, whose willingness to participate in the experiment led them to fill in that omission with the work of their own imagination, and to see Estraven as I [did], as man and woman, familiar and different, alien and utterly human. (6f.)

Eleven years later, she complements this insight by recognizing that she “unnecessarily locked the Gethenians into heterosexuality” by adopting the “naively pragmatic view… that insists that sexual partners must be of opposite sex!” (6).

In their own ways, each of the three works I have examined in this series of posts—Behold the Dreamers, The Refugees, and The Left Hand of Darkness—substantiates then-President Obama’s contention that strong fictional texts foster both an empathic connection with another who may be “very different from you” and a fight for truth in a world that is “complicated and full of grays.” Recognizing how others are shaped by their cultural contexts is a critical step toward a humbling insight into how we are invariably shaped by our own. Or to put this point more in the shape of a paradox: it is only by seeing ourselves as fundamentally other—the contingent product of a culture that has no particular monopoly on truth—that we can come into our wisest possible, most “utterly human” selves.