Hamilton resonates because it speaks, consistently and profoundly, to a deep hunger for wisdom in American society today.

I recently had the pleasure of experiencing first-hand the life story of an “obnoxious arrogant loudmouth” whose “swagger” is “built on a bedrock of total insecurity.” Inordinately proud of his “top-notch brain” but prone to serious acts of misjudgment, this “model New Yorker” commits adultery, then pays hush money to cover his tracks. A great political scandal ensues.

Devotees of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s brilliant musical Hamilton will recognize that I am speaking not of our 45th President, but of the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury. Indeed, to a surprising degree, Miranda’s Hamilton is Donald J. Trump, corrected.

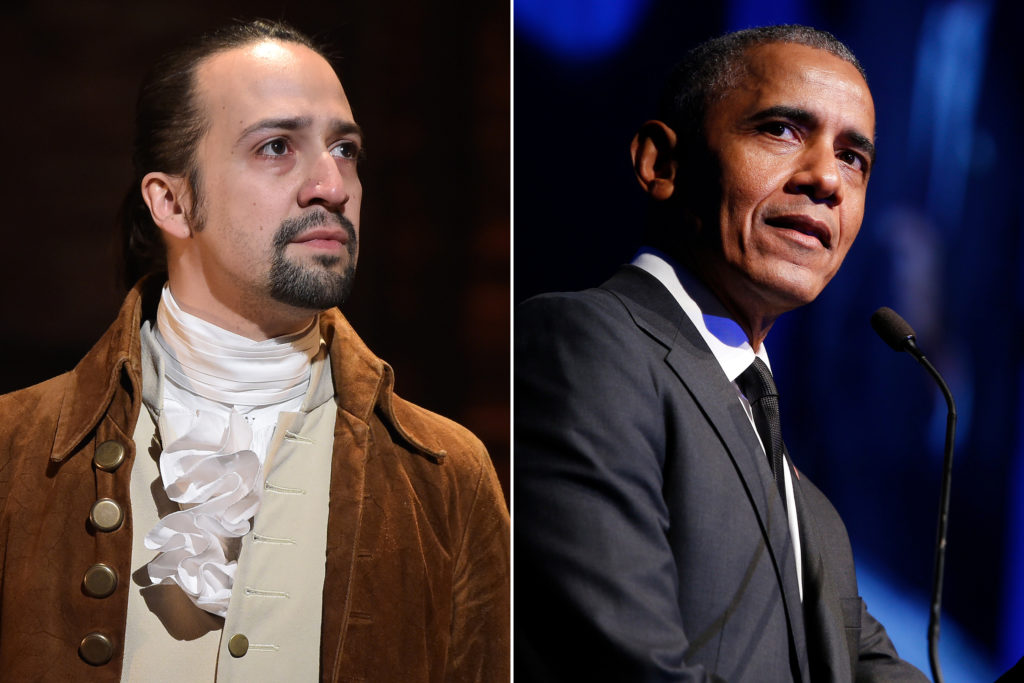

It is tempting to see Hamilton as the product of another, more naively hopeful political time. The musical opened at New York’s Public Theater in February 2015. Both it and the mania that followed—the Hamilton-themed spin classes, the breathless celebrity endorsements, the 16 Tony nominations—clearly bear the mark of the Obama years. Lin-Manuel Miranda—Lin to his fans—performed an early version of Hamilton’s opening number in one of the first cultural events of the Obama White House, in May 2009. Six years later, the nation’s first black President walked onstage after a special performance of Hamilton to say that the musical reminds us that there is a “vital, crazy, kinetic energy… at the heart of America,” that “people can come together, and ideas can move like electricity through them, and the world can change.” Hamilton, Obama quipped, is “the only thing that Dick Cheney and I agree on.”

With its seemingly revolutionary marriage of hip hop and the traditional Broadway musical; the diversity of its casting (including no fewer than three black Presidents); its intention to claim American history by and for “people who don’t look like George Washington and Betsy Ross”; and its insistence that immigrants like Lafayette and Hamilton “get the job done,” Hamilton can easily be read as the love letter of a second-generation Puerto Rican playwright to a second-generation Kenyan president.

To understand Hamilton solely as a product of the Obama years, however, is to miss its long-term impact, as touring productions spread out across the country and around the world, and as the musical eventually makes its way to amateur theaters. Hamilton continues to resonate in the Age of Trump as the story of a deeply flawed political leader in a “world turned upside down”—a world of bitter partisan infighting, pervasive nativism, and rampant disagreement on how to answer those quintessentially Hamiltonian questions: “Are we a nation of states? What’s the state of our nation?” Above all, Hamilton resonates because it speaks, consistently and profoundly, to a deep hunger for wisdom in American society today. As a story of wisdom attained at great personal cost, Hamilton is as prescient as it is timely.

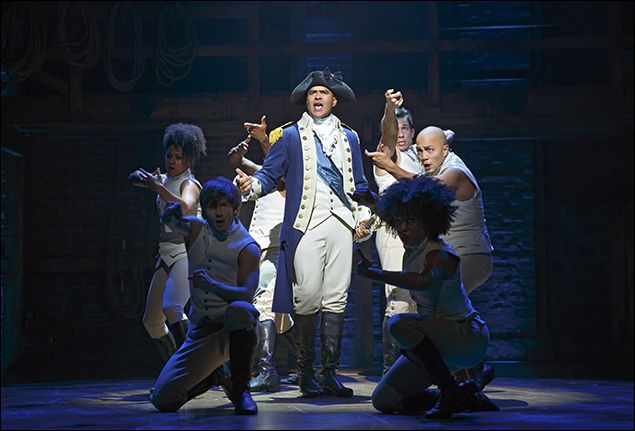

On first encountering Hamilton, we are struck by its artistic freshness, especially its casting of actors of color as founding fathers and mothers and its extensive use of hip hop and battle raps to (among other things) foreground the power of language. And yet Lin’s masterwork is remarkably traditional, both through its sly allusions to musicals past and through its creative reworking of the 19th-century novel of formation.

Just as Balzac recounted the life adventures of a young-man-up-from-the-provinces and Charlotte Brontë those of a young-woman-up-from-poverty, Lin tells of a naïve but determined young-man-up-from-the-Caribbean-islands. The brilliant “My Shot” is not just the classic “‘I want’ song” of musical theater—a paean to ambition by a “young, scrappy and hungry” protagonist who’s discovered that “in New York you can be a new man”—it is also a marker of the worldly wisdom that the young Hamilton has not yet attained, but will over the course of the evening.

To read the novels of a Tolstoy, an Eliot or an Austen is to empathize with multiple characters—to explore the disconnect between their expressed and underlying motives, to recognize their self-defeating behavior, to cringe at their mistakes. When we identify with the character like Anna Karenina, as Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro have recently written, we “put ourselves in her place, feel her difficulties from within, regret her bad choices,” which, for a moment, “become our bad choices.” In other words, reading the novels of the 19th-century psychological realists—though one could say the same of more recent writers like Toni Morrison, Ian McEwan, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Imbolo Mbue—involves a practice in empathy whereby readers “acquire the wisdom to appreciate real people in all their complexity.” The empathic openness to others that comes from reading a strong novel is vital, Morson and Schapiro argue, for both “the disinterested pursuit of truth” and “the preservation of democracy.” As such, it is an ideal antidote to the Trumpist mindset, which too often labels whole peoples as “rapists” or “terrorists”.

Stately, measured, and rising above the ugly partisan fray that increasingly pits Hamilton’s Federalists against Jefferson’s and Madison’s Democratic-Republicans, Lin’s Washington represents wisdom achieved. In “History Has Its Eyes on You,” he shares with the young Hamilton

… what I wish I’d known

When I was young and dreamed of glory.

You have no control.

Who lives, who dies, who tells your story.

Later, as he tells Hamilton that he will not run for reelection in the haunting “One Last Time,” a consummately humble Washington—“too sensible of [his] defects”—speaks of sharing with the American people the “hard won wisdom” he has earned.

Because Hamilton drafted the Farewell Address from which “One Last Time” borrows freely, Lin has him recite it alongside Washington. For much of the musical, however, Hamilton remains deeply flawed: overly proud, arrogant, unrestrained, adulterous, and prone to serious misjudgment. The musical leaves little doubt as to the unwisdom of the so-called Reynolds Pamphlet, in which Hamilton publically confesses to an adulterous affair to clear himself of the charge of treason, with no apparent concern for the pamphlet’s effect on his wife and family. Deep into Act II, an “out of control” Hamilton calls fellow Federalist and then-President John Adams a “fat motherfucker.”

And yet, as witness the musical’s reception and the striking proliferation of A.Ham ball caps on the streets of New York, Hamilton clearly remains the object of our empathy. What Morson and Schapiro suggest of Jane Austen’s heroines applies to Lin’s Hamilton as well: we “experience the complexity of [his] moral problems as if they were [our] own.”

In his essay on anger, Michel de Montaigne wrote: “I do indeed lose my temper in haste and violence, but I do not lose my bearings to the point of hurling about all sorts of insulting words at random and without choice.” There is reason to think that some of President Trump’s supporters like him not despite, but because he hurls about insults in this way. Lin is far cagier, and wiser. I strongly suspect that he cut a long and over-the-top diatribe that Hamilton engages in just prior to the expletive against Adams so as to avoid breaking the viewer’s empathic bond with his protagonist.

No less remarkable than the strength of audience empathy for a flawed Hamilton are the lengths to which Lin went, against the advice of his creative team, to humanize the story’s eventual “villain”, Aaron Burr. Protean and opportunistic where Hamilton remains principled to the end, Burr functions throughout both as Hamilton’s commentator—he often assumes the narrator role—and as his double. Late in Act I, Burr sings a touchingly humble song to his daughter Theodosia, only to have Hamilton join him onstage for a similarly heartfelt tribute to his new son Philip.

But the most profound way in which Hamilton and Burr double one another is in the way their lives exemplify the wisdom that comes in the shadow of death. Although Hamilton grows in wisdom throughout the musical—putting away his martyrdom fantasies in “Yorktown” or practicing compromise in “The Room Where It Happens”—he only fully attains it after Philip dies, in a dual that presages his own. By contrast, Lin’s Burr knows from the outset that he’s the “damn fool” who shot Hamilton. In the musical’s penultimate scene, following Hamilton’s death, we are invited to empathize with Burr as he sings:

I survived, but I paid for it.

Now I’m the villain in your history.

I was too young and blind to see.

I should’ve known….

The world was wide enough for Hamilton and me.

There is a profound, and ultimately wise logic in the fact that, alongside the A.Ham caps for sale in the Richard Rogers Theater’s Hamilton swag shop, you can find nearly identical caps that read A.Burr. Imagine how deeply such a psychologically complex and politically realistic understanding of ostensible villains could revolutionize a certain early morning Twitter feed.

Across many different cultures and across the millennia, wisdom has been associated with the experience that comes with advancing age. Those of us who have begun to live in the shadow of our mortality, the story goes, are better able to see patterns in the flux of experience, to negotiate the complexities of human interaction, and to value the common good over individual ambition. If this story is true—frankly, the evidence cuts both ways—it is all the more remarkable that a group of exceptionally talented 30-somethings could have written a show this wise, a show that Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow has aptly called “American history for grown-ups.”

Much of this wisdom appears to derive from Lin-Manuel Miranda’s life experience. In “My Shot,” Hamilton raps, for the first of three times: “I imagine death so much it feels more like a memory”—a line that Lin has called the most autobiographical line he’s ever written. This lived omnipresence of death helps to explain why Lin might say: “I feel like I have been Burr in my life as many times as I have been Hamilton.”

At a time when an aging President, a changing mediascape, and an increasingly noisy but hollow public sphere conspire to devalue the pursuit of wisdom, it is heartening that this preternaturally wise and exceptionally inventive young playwright-in-from-the-outer-boroughs has found such a satisfying way to sate our continued hunger for it. How better, I would ask, to Make America Great Again?

I’m new on board and am immediately a dedicated fan. It’s a joy to experience such well-written, perspicacious posts. I’ll be watching for further views of/by Peter Starr.