Wisdom does not “lean left” so much as “lean liberal.” If wisdom has a party, it is the party of philosophical liberalism and its historic fellow traveler, liberal education.

Readers of my posts thus far will certainly have noticed my tendency to juxtapose the relative wisdom of Barack Obama to the stunning unwisdom of Donald Trump.

This is not to say that the case for Trump’s wisdom has not been made. In the October 2024 Vice Presidential debate between Republican J.D. Vance and Democrat Tim Walz, moderator Norah O’Donnell invited Vance to address how he and Trump would realize their various economic pledges without ballooning the federal deficit. In so doing, O’Donnell specifically referenced a study by economists at the Wharton School (Trump’s alma mater) who estimated that the ticket’s plans “would increase the nation’s deficit by 5.8 trillion” dollars (Becket). In reply, Vance took issue with all the “PhDs” who “lied” about the benefits of globalization in the 1990s and supposedly mishandled the fight against inflation in the 2020s, repeatedly praising Trump’s “common sense wisdom” (PBS Newshour).

I will confess that my jaw dropped on hearing this, though of course I should have known better.

By yoking “wisdom” with “common sense,” Vance’s rhetoric clearly reflected the MAGAverse’s disdain for expert opinion while echoing the all-too-common assumption that wisdom is fundamentally rooted in the past—in this case, in a mythic time of American “greatness,” prior to the globalist turn, to the ubiquity of women in the workforce, and to the codification of civil rights for minoritized groups. (In a subsequent post, I will argue that the understanding of wisdom in Reinhold Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer serves as an important corrective to this inherently backward-focused conception of wisdom.)

At the same time, Vance’s rhetoric exemplified a characteristically Trumpian reverse projection. For just as Trump himself had done several weeks before in pledging that his administration would be “great for women and their reproductive rights,” Vance claimed for the Republican ticket what polling and much political commentary had suggested to be a relative strength of his Democratic opponents (Piper). In so doing, though it would seem unwittingly, Vance aligned Trump with a long, but relatively forgotten association of “wisdom” with “cunning”, variously illustrated by the Greek goddess Metis and by any number of African trickster figures (Curnow 17, 39) .

If nothing else, Vance’s evocation of his running mate’s “common sense wisdom” exemplifies “wisdom’s” status as a floating signifier. Like “democracy” and “freedom”—ideals that both tickets in the 2024 campaign clearly but variously claimed to serve—“wisdom” often points to a characteristic of great value and meaning that nonetheless functions without a stable referent. It is the goal of my work here, and of much of the philosophical and psychological work on which I have relied, to set boundaries on just how far “wisdom” is allowed to float.

All of this raises the question: what is the political valence of wisdom as I have come to understand it? Or, to put the question more pointedly, does wisdom lean left?

As Robert Sternberg has argued, it is impossible to speak of someone or something as “wise” without invoking a set of underlying values, inasmuch as values “contribute… to how one defines a common good” (“Balance Theory”). Sternberg’s insight helps to explain how the significance of “wisdom” can float so radically, since Vance’s purported values differ markedly from his opponents’. But it also helps to sharpen my question. Specifically, are the values that support my definition of wisdom—not to mention that of Sternberg and recent academic psychology—essentially left-leaning?

It is tempting to answer “yes”. Imbued as they are by evangelical habits of mind, many on the right in America today view wisdom as that which emanates from God or his proxies, including (somewhat incongruously to many of us) Donald J. Trump. To them, wisdom is received truth. Faith surely involves struggles, but not necessarily the long (and by nature incomplete) struggles on which wisdom depends—struggles to grasp the complexities of the world, to understand and empathize with those whose values may differ markedly from one’s own, to defend the notion that facts matter, to value science, and to steadfastly pursue the common good, not simply the view of one’s tribe.

In recent years, “empathy” and its fellow traveler “social justice” have become demonstrably liberal mantras. In a piece for Ireland’s The University Times published prior to the full backlash against so-called wokeism, Eliana Jordan writes:

Underpinning this obvious desire to make the world a more equal place, there is one single abiding principle driving every effort to make circumstances better for less privileged members of society: empathy…. Being ‘woke’ is actually [a] covert way of describing the empathy we’ve adopted in order to facilitate a more equitable culture.

As for the left’s seemingly greater appetite for complexity, I am reminded of neuroscientist David Amodio’s much-discussed 2007 study of the political brain, which found that self-described liberals, in the face of conflict, “report higher tolerance of ambiguity and complexity, and greater openness to new experiences” as compared to self-styled conservatives, who demonstrate greater need for “order, structure, and closure” (1246).

But the comforting assumption that today’s left is necessarily wiser than today’s right should give us pause, if only because the wokeness to which Jordan refers gave rise toward the end of this past decade to a decidedly non-empathic cancel culture, whose “cannibalistic maw” (in the words of reproductive rights activist Loretta Ross) tended to foreclose the possibility of meaningful dialogue and personal growth, and so risked devolving into “just ruthless hazing.”

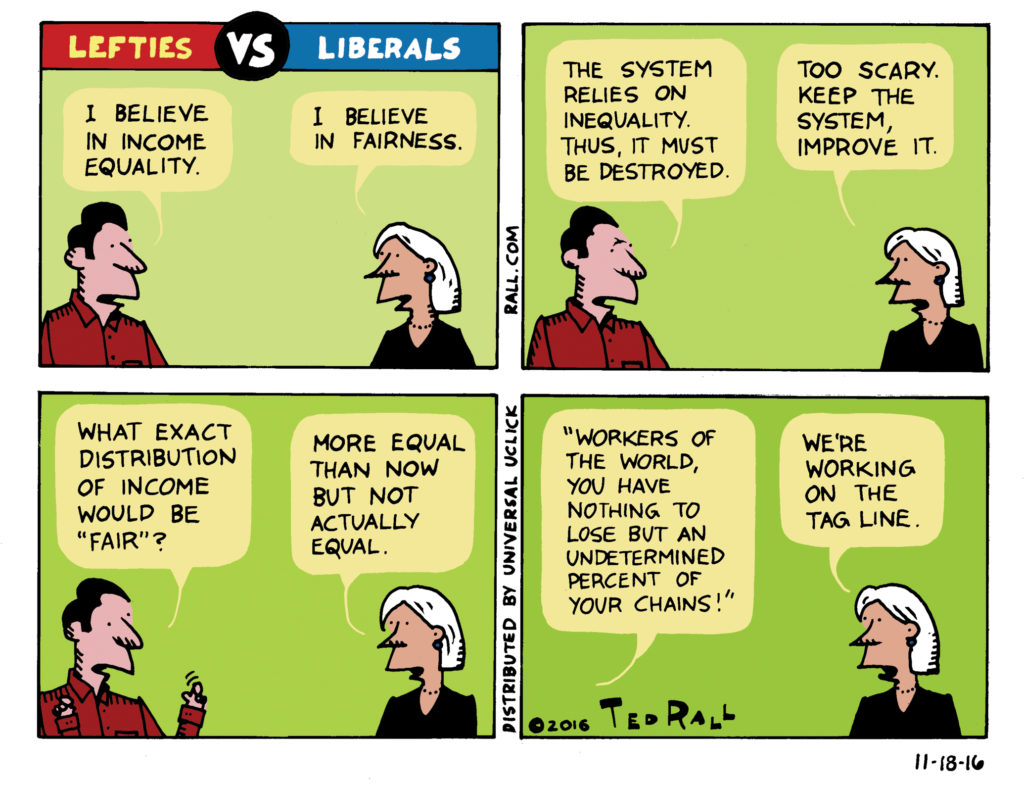

In contemporary political discourse, we commonly equate “leftist” and “liberal”. In fact, I just did it. Over the past decade, however, this equation has become increasingly problematic, as has the traditional division of our political sphere into “left” and “right”. As this chapter will show, wisdom does not “lean left” so much as “lean liberal.” If wisdom has a party, it is the party of philosophical liberalism and its historic fellow traveler, liberal education.

In the two posts that follow, I explore the confluence of wisdom and liberal ideals, with specific reference to Adam Gopnik’s A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism and Martha Nussbaum’s Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education.