When I think about how I understand my role as citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to the position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy.

Barack Obama, in Conversation with Marilynne Robinson

We are living through an era of extraordinary nativist backlash across the globe. Populist leaders—from Donald Trump and Narendra Modi to Marine Le Pen and Viktor Orbán—obtain great power by stoking fears of globalization, job displacement, the loss of cultural privilege, a watering down of national identity, and miscegenation.

Among those who consider themselves to be true representatives of their nation and culture, nearly all of whom are the descendants of one-time immigrants, these politicians skillfully exploit a growing feeling of their being outsiders in their own countries. A 2017 survey by PRRI and The Atlantic, for instance, found that white working-class voters who said they “often feel like a stranger in their own land” were 3.5 times more likely to have supported Donald Trump than Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election; those who “favored deporting immigrants living in the country illegally” were 3.3 times more likely to have done so (Cox). In the run-up to the 2024 election, Trump and his running mate J.D. Vance stoked the truly absurd story that (predominantly legal) Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio were killing and eating their neighbors’ dogs and cats.

Journalist James Fallows, whose Our Towns: A Journey into the Heart of America usefully complicates common perceptions of red state America, has pointed to a familiar paradox at the heart of such numbers:

Steve King, a Republican who is the most outspokenly anti-immigrant member of Congress, represents a district in Iowa that is 93 percent white; representatives from districts along the U.S.-Mexico border, Republican and Democrat alike, are more relaxed about the immigrant ‘threat’ and either outright oppose or only tepidly support plans to ‘build the wall.’

A logical conclusion to be drawn from Fallows’ data point, and from similar arguments over the years, is that exposure to the experienc of cultural dislocation—either directly or indirectly—actually mitigates the fear thereof. As is well known to readers who have spent appreciable time in cultures dramatically different from their own, the best vaccine against the feeling of being a stranger in one’s own land is the experience of having been a stranger in someone else’s.

In a wide-ranging conversation with novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson in September of 2015, then-President Barack Obama expressed concern “about people not reading novels anymore,” going on to remark:

When I think about how I understand my role as citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to the position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy. It has to do with being comfortable with the notion that the world is complicated and full of grays, but there’s still truth there to be found, and that you have to strive for that and work for that. And the notion that it’s possible to connect with some[one] else even though they’re very different from you.

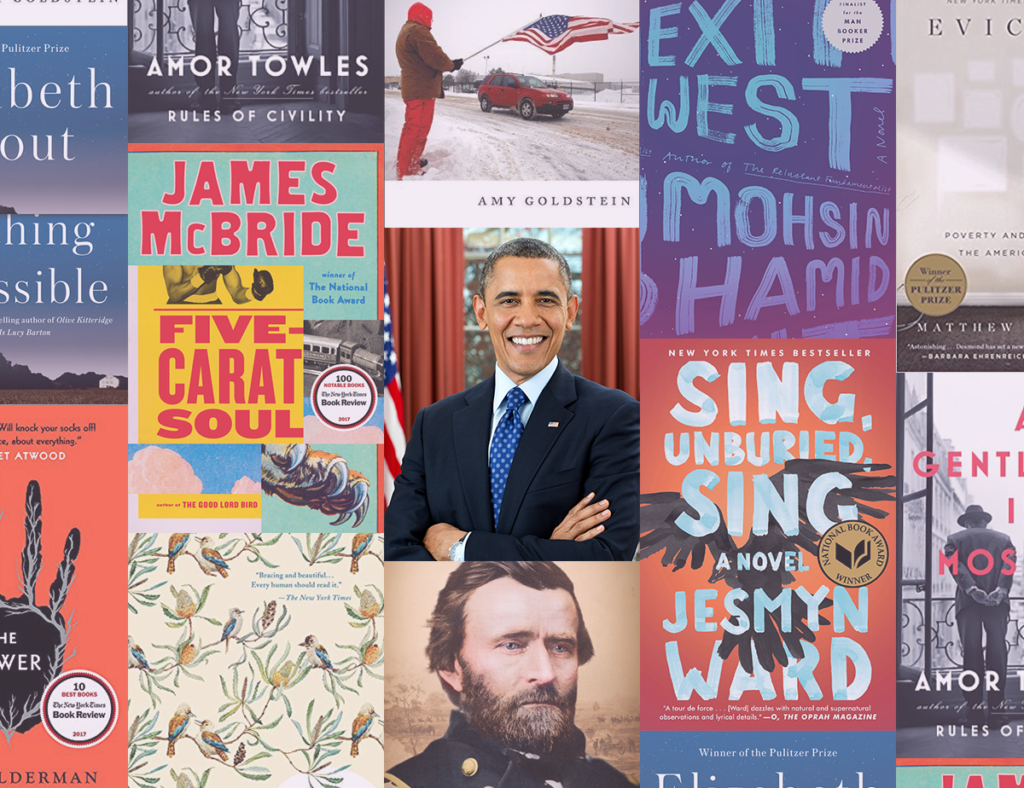

Photo: 12 of Obama’s Favorite Books, Off the Shelf

This extraordinary statement speaks to all five of the markers of wisdom I am tracking here:

- An appreciation for complexity in both its cognitive and ethical forms;

- Attention to how particular social, cultural, economic, and/or religious contexts shape the actions and values of individuals—be they historic, contemporary or fictional;

- Empathic care for the other;

- A deep-seated sense for the values of community and social justice; and

- An embrace of intellectual humility.

At the same time, Obama’s expression of concern served as an intervention, conscious or not, in an ongoing debate within the discipline of psychology. In 2013, New School psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano published in Science a widely-reported study showing that the reading of literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction and nonfiction, led to improvements in “the inference and representation of others’ beliefs and intentions” and “the ability to detect and understand others’ emotions”—i.e., cognitive and affective “theory of mind” (377).

At a time when the value of humanistic study seemed under assault from all quarters—including, just a few months later, from President Obama himself—this finding was widely embraced by humanists as confirmation of a causal linkage between literary reading and the development of empathic understanding, “the holy grail in theoretical and empirical investigations into the effects of reading literature” (Jaschik; Koopman 62).

Subsequent studies have largely failed to replicate Kidd and Castano’s results, and it is well worth remembering that extraordinary empathy can serve ill purposes, as the character of Shakespeare’s Iago clearly attests (Siegel). Yet two related findings remain widely accepted in psychological circles: 1) that readers with greater lifetime exposure to literature, as measured by an author recognition test, tend to respond more empathically to literary texts, and 2) that reading narrative fiction is particularly effective in reducing prejudice in readers not otherwise prone to embrace the perspectives of individuals in so-called outgroups (Koopman 76, Frankel, Johnson et al. 593).

One important caution to emerge from these debates is that the relationship between exposure to literature and empathic understanding may be one of positive correlation, not causation. Who is to say, for instance, that individuals prone to cognitive and affective empathy are not more likely to become lifelong readers of fiction?

With that caution in mind, the three posts that follow focus on how the unfolding of narrative, and the reader’s implication in the process of narrative sense-making, enables empathy and empathic connection, and the wisdom that follows therefrom.

I begin with two relatively recent works of fiction on immigrant experience in America: Imbolo Mbue’s 2016 novel, Behold the Dreamers, and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 2017 story collection, The Refugees. In both works, a timely focus on migration flows in the age of globalization is buttressed by the age-old trope of the journey toward wisdom: for their characters, certainly, but also for their readers. In their depiction of characters athwart two cultures, their evocations of readerly empathy, and their respective stakes in ethical complexity, Behold and Refugees bring the readerly journey very much into play.

I then conclude with a reading of Ursula K. Le Guin’s masterful “thought experiment,” The Left Hand of Darkness, which highlights its protagonist’s humbling encounter—and, by extension, the reader’s—with a markedly different culture and form of sexual embodiment. Here, as in the case of the previous two works, the author lays traps for her reader, such that we emerge from the narrative with a different perspective from the one we are invited to hold at its outset. In a genre—science fiction—that has historically provided far too many representations of the alien as Other, Le Guin gives us a psychologically rich, culturally informed, and deeply empathic version of the dialogic journey to wisdom.

My thesis throughout is that the reading of strong narratives recounting migrants’ experiences of dramatic personal dislocation is a privileged way (in the words of geographer Dragos Simandan) “to escape being spellbound by the hypnotic trance of any given culture” (393). The experience of reading literary fiction—even the notably wise War and Peace—cannot match the time scale of the life experience on which wisdom is commonly understood to depend. Still, it remains a valuable proxy thereof.