This is the first in a series

The quest for wisdom is a physical as well as intellectual undertaking…. [T]he early history of wisdom unfolded on the road.

Stephen S. Hall, Wisdom: From Philosophy to Neuroscience

We are living through a time of extraordinary nativist backlash, most tellingly emblematized in the U.S. by the candidacy, then presidency, of Donald J. Trump. A 2017 survey by PRRI and The Atlantic found that white working-class voters who said they “often feel like a stranger in their own land” were 3.5 times more likely to have supported Trump than Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. Those who “favored deporting immigrants living in the country illegally” were 3.3 times more likely to have done so.

A recent piece by James Fallows points to a familiar paradox at the heart of such numbers:

Steve King, a Republican who is the most outspokenly anti-immigrant member of Congress, represents a district in Iowa that is 93 percent white; representatives from districts along the U.S.-Mexico border, Republican and Democrat alike, are more relaxed about the immigrant ‘threat’ and either outright oppose or only tepidly support plans to ‘build the wall.’

A logical conclusion to be drawn from Fallows’ data point, and from similar arguments over the years, is that exposure to the experience of cultural dislocation—either directly or indirectly—actually mitigates the fear thereof. As is well known to readers who have spent appreciable time in cultures dramatically different from their own, the best vaccine against the feeling of being a stranger in one’s own land is the experience of having been a stranger in someone else’s.

One of my aims with WisCult is to examine pockets of significant cultural wisdom in an age marked by great social and political ‘unwisdom’. In this series, I will read contemporary narratives of migration to show how a timely focus on migration flows in the age of globalization is buttressed by the age-old trope of the journey toward wisdom: for their characters, certainly, but also for their readers. Indeed, the reading of strong narratives recounting the migrant’s experience of dramatic personal dislocation is a privileged way (in the words of geographer Dragos Simandan) “to escape being spellbound by the hypnotic trance of any given culture.”

In this blog’s founding post, I argued that teaching for wisdom in the Age of Trump demands four interrelated strategies. Today more than ever, it is beholden upon us: 1) to teach our students to acknowledge and appreciate complexity in both its cognitive and ethical forms; 2) to help them see how the actions and value of individuals—be they historic, contemporary or fictional—are shaped by their particular social, cultural, economic and/or religious contexts; 3) to foster in our students an empathic care for the other and a deep-seated sense of social justice; and 4) to embrace cognitive humility. Contemporary narratives of migration tend, as a matter of course, to foreground the second and third of these strategies, those of “cognitive empathy” and “affective empathy” respectively. But all four strategies can and should be brought to bear in the reading of such narratives.

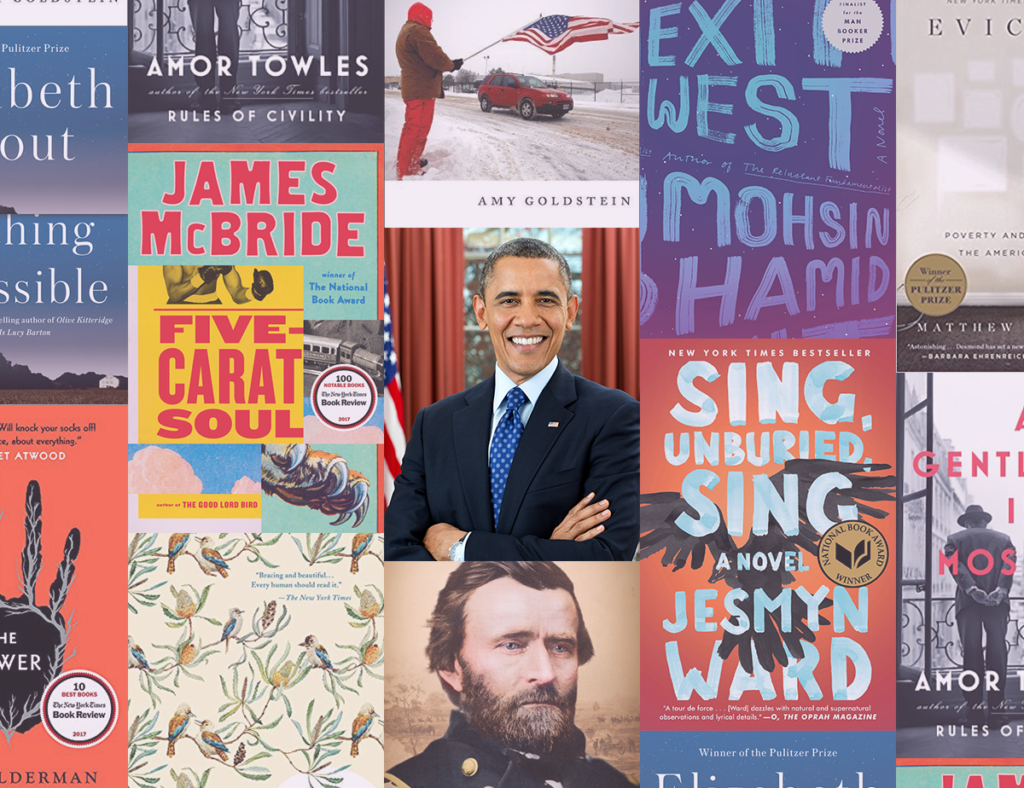

In a wide-ranging conversation with novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson in September of 2015, then-President Barack Obama expressed concern “about people not reading novels anymore,” going on to remark:

When I think about how I understand my role as citizen, setting aside being president, and the most important set of understandings that I bring to the position of citizen, the most important stuff I’ve learned I think I’ve learned from novels. It has to do with empathy. It has to do with being comfortable with the notion that the world is complicated and full of grays, but there’s still truth there to be found, and that you have to strive for that and work for that. And the notion that it’s possible to connect with some[one] else even though they’re very different from you.

This extraordinary statement not only evokes each of the four markers of wisdom above—an appreciation for complexity, the embrace of cultural difference, empathy for the other, and (in its overall tone) cognitive humility—it intervened, as Obama was likely aware, in an ongoing debate within the discipline of psychology.

In 2013, New School psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano published in Science a widely-reported study showing that the reading of literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction and nonfiction, led to improvements in “the inference and representation of others’ beliefs and intentions” and “the ability to detect and understand others’ emotions”—i.e., cognitive and affective “theory of mind.” At a time when the value of humanistic study seemed under assault from all quarters—including, just a few months later, from President Obama himself—this finding was widely embraced by humanists as confirmation of a causal linkage between literary reading and the development of empathic understanding, “the holy grail in theoretical and empirical investigations into the effects of reading literature.” Subsequent studies have largely failed to replicate Kidd and Castano’s results, and it is well worth remembering that extraordinary empathy can serve ill purposes, as the character of Shakespeare’s Iago clearly attests. Yet two related findings remain widely accepted in psychological circles: 1) that readers with greater lifetime exposure to literature, as measured by an author recognition test, tend to respond more empathically to literary texts, and 2) that reading narrative fiction is particularly effective in reducing prejudice in readers not otherwise prone to embrace the perspectives of individuals in so-called outgroups.

One important caution to emerge from these debates is that the relationship between exposure to literature and empathic understanding may be one of positive correlation, not causation. (Who is to say, for instance, that individuals prone to cognitive and affective empathy are not more likely to become lifelong readers of fiction?) In this series, I will examine how the unfolding of narrative, and the reader’s implication in the process of narrative sense-making, enables empathy and empathic connection, and the wisdom that follows therefrom. Understanding how narratives of migration contribute to our seemingly imperiled store of collective wisdom, in other words, means paying particular attention to three related ‘journeys’: 1) the physical journey that characters undertake in migrating to another country, 2) their complex cognitive and ethical journeys over the course of the narrative, and 3) the reader’s own journey along wisdom’s four dimensions as the narrative unfolds. The experience of reading literary fiction—even the notably wise War and Peace—cannot match the time scale of the life experience on which wisdom is commonly understood to depend. Still, it remains a significant (and no less valuable) proxy thereof.