At a time when white masculinity has driven what Barbara Tuchman called “the persistence of unwisdom in government” to new depths, narratives like Mbue’s and Nguyen’s could not be more important, nor more welcome.

This is the third in a series. You’ll find the series’ conceptual framework in Part 1 here and the reading of Behold the Dreamers in Part 2 here.

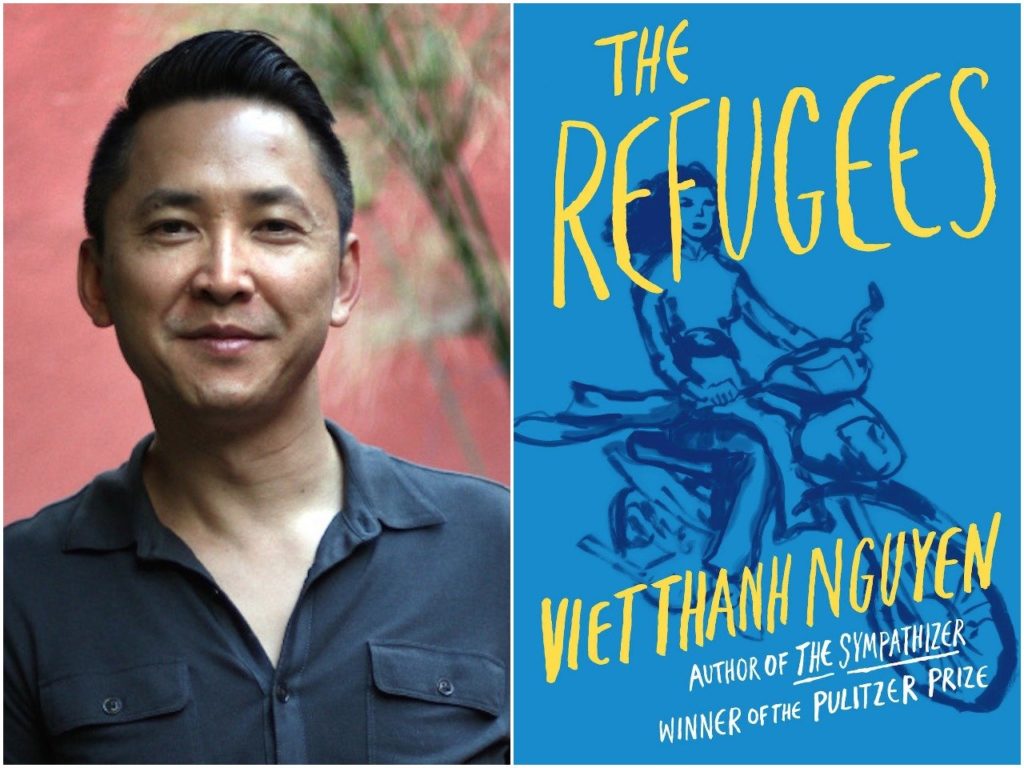

The Refugees is Viet Thanh Nguyen’s second book, following on his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Sympathizer. Most of the volume’s eight stories, composed over the better part of two decades, depict the disorientation experienced by Vietnamese refugees in the U.S.—athwart two cultures but at home in neither; struggling to attain a sense of individuality in the face of an “astigmatism” whereby all Asians look the same to American eyes; and perennially conscious that it is “un-American to be a refugee” (80, 212). Nguyen’s refugees are other, even to themselves—as exemplified by that moment in “The Other Man” when Liem sees his reflection in a nighttime window, without recognizing himself (46). In sum, the collection is masterful in the way it builds readerly compassion for characters whom Joyce Carol Oates has aptly called “emotional convalescents, groping their way to an understanding of their woundedness.”

By virtue of being a novel, Behold the Dreamers has the luxury of drawing the reader deeply into the emotional development and ethical struggles of its characters, as they negotiate significant cultural divides. Indeed, Mbue’s work sometimes reads like a succession of deeply ambivalent ethical case studies. Although richly evocative of both cognitive and affective empathy—the second and third of my elements of wisdom—the stories of The Refugees are less about their characters’ coming into consciousness over time, and more about the reader’s.

I have suggested that the fourth and final way to teach for wisdom in a seemingly unwise age is to embrace cognitive humility, consistent with Socrates’ remark in Plato’s Apology: “I am wiser than he is to this small extent that I do not think that I know what I do not know” (25, section 21d). Because precepts and injunctions to wisdom often fall on deaf ears, and because humiliation is not conducive to humility (despite a shared etymology), it is surely the case that the best way to teach cognitive humility is to embody it oneself. That said, ‘wise’ narratives commonly set traps for readers, to foster readerly humility by catching us in our deeply faulty assumptions.

The best example of this in Behold the Dreamers involves the character of Cindy Edwards. Because Cindy appears so fully at home in the privileged worlds of New York City and Southampton, Neni assumes (as I suspect do most readers) that she had “never known what it’s like to worry about money” (29). Midway through the novel, however, we learn that Cindy was the product of a rape, that she was brought to term by governmental fiat, and that she spent her childhood being beaten by a mother who saw her rapist’s face in that of her child and who never failed to remind Cindy that she “was just a piece of shit” (135, 123f.). As they force us to reevaluate all we thought we knew about a given character or situation, such moments remind us of the folly of thinking we know what we in fact do not.

The Refugees deploys this technique to great effect. The book’s opening story, “Black-Eyed Women,” derives much of its power from the way it withholds the gender of its ghostwriter protagonist, still more belatedly revealing that she has been raped by pirates. “The Transplant” hinges on the discovery that the protagonist’s counterfeiter friend is himself a counterfeit, though in a way that speaks to the reality of a multi-ethnic present:

“Oh!” Arthur gasped. “I knew it! I knew you were Chinese!”

“But I was born in Vietnam, and I’ve never been to China…. I can barely speak Chinese. So what does that make me? Chinese or Vietnamese? Both? Neither?” (93)

A story about nothing so much as self-identity, “The Americans” waits a full six pages to reveal that its cranky and stereotypically jingoistic Southern father is black, and has suffered throughout his life from “the look in people’s eyes that said What are you doing here?” (132).

More often than not, Nguyen’s slow reveals do more than catch us as readers in our decidedly unhumble rush to judgement; they underscore the ethical complexity of action in the world. In “War Years,” the narrator’s shopkeeper mother resists the seemingly extortionist demands of a Mrs. Hoa, who seeks funds for an army of former South Vietnamese fighters training in Thailand, only to give in on learning of Mrs. Hoa’s woundedness—the wartime loss of her husband and sons (69f.). In the haunting “I’d Want You to Love Me,” the wife of a professor sliding inexorably into dementia submits to being called by another woman’s name—knowing, “not for the first time, that it wasn’t she who was the love of his life” (123).

I have spoken, echoing Roland Barthes, of the ending of Behold the Dreamers as “pensive” (S/Z 215-216). The Jonga family’s return to Cameroon is markedly bittersweet. Jende returns neither as the “conqueror” he envisions nor as suffering from “the shame and the indignity” he fears (19, 60). Wavering “between joy and sorrow” for her children, Neni rushes out to buy American goods prior to their departure, so as to “preserve their American aura” and ensure that Jende remains faithful (361, 348). In the end, the Jongas benefit from the structural privilege of a favorable exchange rate, with their modest savings in dollars making them, once back in Cameroon, “millionaires many times over” (352).

“Fatherland,” the final story in Nguyen’s The Refugees, deploys the technique of the slow reveal to tell a similar allegory of structural privilege. Yet it does so in a mode that’s more defiant than bittersweet, more self-assertive than self-denying. For much of the story, the Saigon-based Phuong admires her “noble, kindly” and “independent” Americanized stepsister, Vivien. Phuong’s double within an oddly twinned family structure, Vivien is known to the restless and ambitious Phuong as an “unmarried pediatrician who had backpacked solo through Western Europe and vacationed in Hawaii” (183, 186).

But when Phuong confides to Vivien that she wants “to be like” her, Vivien is forced to come clean: she is not a doctor, as her mother had told Phuong’s family, but an unemployed receptionist who had been let go after sleeping with her boss, and who had only been able to afford to wine and dine Phuong’s family during her two-week visit to Vietnam because, “[i]n America, they pay you extra when they fire you” (200, 202). The story ends with a newly defiant Phuong burning photographs of Vivien’s visit and reasserting her vow to leave her family, and a father who “loved Vivien more than her”—as the ashes of the photographs vanish into the “inverted blue bowl” of the Saigon sky.

All too often, we assume that arguing for wisdom’s place in discussions around culture means defending the privilege of a predominantly male, overwhelmingly white literary and philosophical canon. The narratives of migration that I have examined thus far—to which one could certainly add Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West and others besides—belie this assumption. At a time when white masculinity has driven what Barbara Tuchman called “the persistence of unwisdom in government” to new depths, narratives like Mbue’s and Nguyen’s could not be more important, nor more welcome.